If there is any notion widespread among the Hindus and understood by every man and woman adult or old, mature or immature it is that of the Kali Yuga. They are all aware of the fact that the present Yuga is Kali Yuga and that they are living in the Kali Yuga. The theory of Kali Yuga has a psychological effect upon the mind of the people. It means that it is an unpropitious age. It is an immoral age. It is therefore an age in which human effort will not bear any fruit. It is therefore necessary to inquire as to how such a notion arose. There are really four points which require elucidation. They are (1) What is “Kali Yuga?, (2) When did Kali Yuga begin ?, (3) When is the Kali Yuga to end ? and (4) Why such a notion was spread among the people.

I

To begin with the first point. For the purposes of this inquiry it is better to split the words Kali Yuga and consider them separately. What is meant by Yuga ? The word Yuga occurs in the Rig-Veda in the sense of age, generation or tribe as in the expressions Yuge Yuge (in every age), Uttara Yugani (future ages), Uttare Yuge (later ages) and Purvani Yugani (former ages) etc. It occurs in connection with Manushy, Manusha, Manushah in which case it denotes generations of men. It just meant ages. Various attempts are made to asertain the period the Vaidikas intended to be covered by the term ‘Yuga’. Yuga is derived from the Sanskrit root Yuj which means to join and may have had the same meaning as the astronomical term ‘conjunction’. Prof. Weber suggests that the period of time known as Yuga was connected with four lunar phases.

Following this suggestion Mr. Rangacharya1 has advanced the theory that “in all probability the earliest conception of a Yuga meant the period of a month from new-moon when the Sun and the Moon see each other i.e., they are in conjunction”. This view is not accepted by others. For instance, according to Mr. Shamshastry2 the term Yuga is in the sense of a single human year as in the Setumahatmya which is said to form part of the Skanda Purana. According to the same authority it is used in the sense of a Parva or half a lunation, known as a white or dark half of a lunar month.

All these attempts do not help us to know what was the period which the Vaidikas intended to be covered by a Yuga.

While in the literature of the Vaidikas or theologians there is no exactitude regarding the use of the term Yuga in the literature of the astronomers (writers on Vedanga Jyotish) as distinguished from the Vaidikas the word Yuga connotes a definite period. According to them, a Yuga means a cycle of five years which are called (1) Samvatsara, (2) Parivatsara, (3) Idvatsara, (4) Anuvatsara and (5) Vatsara.

Coming to Kali it is one of the cycles made up of four Yugas: Krita, Treta, Dwapar and Kali. What is the origin of- the term Kali ? The terms Krita, Treta, Dwapar and Kali are known to have been used in the three different connections. The earliest use of the term Kali as well as of other terms is connected with the game of dice.

From the Rig-Veda it appears that the dice piece that was used in the game was made of the brown fruit of the Vibhitaka tree being about the size of a nutmeg, nearly round with five slightly flattened sides. Later on the dice was made of four sides instead of five. Each side was marked with the different numerals 4, 3, 2 and 1. The side marked with 4 was called Krita, with 3 Treta, with 2 Dwapara and with 1 Kali. Shamshastry gives an account of how a game of dice formed part of sacrifice and how it was played. The following is his account3:

“Taking a cow belonging to the sacrificer, a number of players used to go along the streets of a town or village, and making the cow the stake, they used to play at dice in different batches with those who deposited grain as their stake. Each player used to throw on the ground a hundred or more Cowries (shells), and when the number of the Cowries thus cast and fallen with their face upwards or downwards, as agreed upon, was exactly divisible by four then the sacrificer was declared to have won; but if otherwise he was defeated. With the grain thus won, four Brahmans used to be fed on the day of sacrifice.”

Professor Eggling’s references1 to the Vedic literature leave no doubt about the prevalence of the game of dice almost from the earliest time. It is also clear from his references that the game was played with five dice four of which were called Krita while the fifth was called Kali. He also points out that there were various modes in which the game was played and says that according to the earliest mode of playing the game, if all the dice fell uniformly with the marked sides either upwards or downwards then the player won the game. The game of dice formed part of the Rajasuya and also of the sacrificial ceremony connected with the establishment of the sacred fire.

These terms—Krita, Treta, Dwapara and Kali—were also used in Mathematics. This is clear from the following passage from Abbayadevasuri’s Commentary on Bhagvati Sutra a voluminous work on Jaina religion.

“In mathematical terminology an even number is called ‘Yugma’, and an odd number ‘Ojah’. Here there are, however, two numbers deserving of the name ‘Yugma’ and two numbers deserving of the name ‘Ojah’. Still, by the word ‘Yugma’ four Yugmas i.e., four numbers are meant. Of them i.e., Krita-yugma: Krita means accomplished, i.e., complete, for the reason that there is no other number after four, which bears a separate name (i.e., a name different from the four names Krita and others). That number which is not incomplete like Tryoja and other numbers, and which is a special even number is Kritayugma. As to Tryoja: that particular odd number which is uneven from above a Krityugma is Tryoja. As the Dwaparayugma:—That number which is another even number like Krityugma, but different from it and which is measured by two from the beginning or from above a Krityugma is Dwaparayugma— Dvapara is a special grammatical word. As to Kalyoja:—That special uneven number which is odd by Kali, i.e., to a Kritayugma is called Kalyoja. That number etc. which even divided by four, ends in complete division, Krityugma. In the series of numbers, the number four, though it need not be divided by four because it is itself four, is also called Krityugma.”

Shamshastry2 mentions another sense in which these terms are used. According to him, they are used to mean the Parvas of those names, such as Krita Parva, Treta Parva, Dwapara Parva and Kali Parva. A Parva is a period of 15 tithis or days otherwise called Paksha. For reasons connected with religious ceremonies the exact time when a Parva closed was regarded as important. It was held that the Parvas fell into four classes according to the time of their closing. They were held to close either (1) at Sunrise, (2) at one quarter or Pada of the day, (3) after 2 quarters or Padas of the day or (4) at or after three quarters or Padas of the day. The first was called Krita Parva, the second Treta Parva, the third Dwapara Parva and the fourth Kali Parva.

Whatever the meaning in which the words Kali and Yuga were used at one time, the term Kali Yuga has long since been used to designate a unit in the Hindu system of reckoning time. According to the Hindus there is a cycle of time which consists of four Yugas of which the Kali Yuga forms one. The other Yugas are called Krita, Treta and Dwapar.

II

When did the present Kali Yuga begin ? There are two different answers to the question.

According to the Aitereya Brahmana it began with Nabhanedishta son of Vaivasvata Manu. According to the Puranas it began on the death of Krishna after the battle of Mahabharata.

The first has been reduced to time term by Dr. Shamshastry1 who says that Kali Yuga began in 3101 B.C. The second has been worked out by Mr. Gopal Aiyer with meticulous care. His view is that the Mahabharat War commenced on the 14th of October and ended on the night of 31st October 1194 B.C. He places the death of Krishna 16 years after the close of the war basing his conclusion on the ground that Parikshit was 16 when he was installed on the throne and reading it with the connected facts namely that the Pandavas went of Mahaprasthan immediately after installing Parikshit on the throne and this they did on the very day Krishna died. This gives 1177 B.C. as the date of the commencement of the Kali Yuga.

We have thus two different dates for the commencement of the Kali Yuga 3101 B.C. and 1177 B.C. This is the first riddle about the Kali Yuga. Two explanations are forthcoming for these two widely separated dates for the commencement of one and the same Yuga. One explanation is 3101 B.C. is the date of the commencement of the Kalpa and not of Kali and it was a mistake on the part of the copyist who misread Kalpa for Kali and brought about this confusion. The other explanation is that given by Dr. Shamshastry. According to him there were two Kali Yuga Eras which must be distinguished, one beginning in 3101 B.C. and another beginning in 1260 or 1240. B.C. The first lasted about 1840 or 1860 years and was lost.

III

When is the Kali Yuga going to end ? On this question the view of the great Indian Astronomer Gargacharya in his Siddhanta when speaking of Salisuka Maurya the fourth in succession from Asoka makes the following important observation1:

“Then the viciously valiant Greeks, after reducing Saketa, Panchala country to Mathura, will reach Kusumadhwaja (Patna): Pushpapura being taken all provinces will undoubtedly be in disorder. The unconquerable Yavanas will not remain in the middle country. There will be cruel and dreadful war among themselves. Then after the destruction of the Greeks at the end of the Yuga, seven powerful Kings reign in Oudha.”

The important words are “after the destruction of the Greeks at the end of the Yuga”. These words give rise to two questions (1) which Yuga Garga has in mind and (2) when did the defeat and destruction of the Greeks in India take place. Now the answers to these questions are not in doubt. By Yuga he means Kali Yuga and the destruction and defeat of the Greeks took place about 165 B.C. It is not mere matter of inference from facts. There are direct statements in chapters 188 and 190 of the Vanaparva of the Mahabharata that the Barbarian Sakas, Yavanas, Balhikas and many others will devastate Bharatvarsna ‘at the end of the Kali Yuga’.

The result which follows when the two statements are put together is that the Kali Yuga ended in 165 B.C. There is also another argument which supports this conclusion. According to the Mahabharata, Kali Yuga was to comprise a period of one thousand years2. If we accept the statement that the Kali Yuga began in 1171 B.C. and deduct one thousand years since then we cannot escape the conclusion that Kali Yuga should have ended by about 171 B.C. which is not very far from the historical fact referred to by Garga as happening at the close of the Kali Yuga. There can therefore be no doubt that in the opinion of the chief Astronomer3, Kali Yuga came to end by about 165 B.C. What is however the position ? The position is that according to the Vaidika Brahman’s Kali Yuga has not ended. It still continues. This is clear from the terms of Sankalpa which is a declaration which every Hindu makes even today before undertaking any religious ceremony. The Sankalpa is in the following terms1:

“On the auspicious day and hour, in the second Parardha of First Bramha, which is called the Kalpa of the White Boar, in the period of Vaivasvata Manu, in the Kali Yuga, in the country of Jambudvipa in Bharatavarsha in the country of Bharat, in the luni-solar cycle of the sixty years which begins with Pradhava and ends with Kshaya or Akshaya and which is current, as ordained by Lord Vishnu, in the year (name), of the cycle, in the Southern or the Northern Ayana, as the case may be, in the white or dark half, on the Tithi, I (name) begin to perform the rite (name) the object of pleasing the Almighty.”

The question we have to consider is why and how the Vedic Brahmins manage to keep the Kali Yuga going on when the astronomer had said it was closed. The first thing to do is to ascertain what is the original period of the Kali Yuga ? According to the Vishnu Purana:

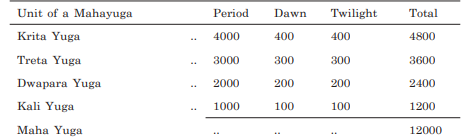

“The Kritayuga comprises 4000 years, the Treta 3000; the Dwapara 2000 and the Kali 1000. Thus those that know the past have declared.”

Thus Kali Yuga originally covered a period of 1000 years only. It is obvious that even on this reckoning the Kali Yuga should have ended long ago even according to the reckoning of the Vedic Brahmins. But it has not. What is the resason ? Obviously, because the period originally covered by the Kali Yuga came to be lengthened. This was done in two ways.

Firstly, it was done by adding two periods called Sandhya and Sandhyamsa before and after the commencement and the end of a Yuga. Authority for this can be found in the same passage of the Vishnu Purana already referred to and which reads as follows:

“The period that precedes a Yuga is called Sandhya. and the period which comes after a Yuga is called Sandhyamsa, which lasts for a like period. The intervals between these Sandhyas and Sandhyamsas are known as the Yugas called Krita, Treta and the like.”

What was the period of Sandhya and Sandhyamsa ? Was it uniform for all the Yugas or did it differ with the Yuga. Sandhya and Sandhyamsa periods were not uniform. They differed with each Yuga. The following table gives some idea of the four Yugas and their Sandhya and Sandhyamsa—

The Kali Yuga instead of remaining as before a period of 1,000 years was lengthened to a period of 1,200 years by the addition of Sandhya and Sandhyamsa.

Secondly a new innovation was made. It was declared that the period fixed for the Yugas was really a period of divine years and not human years. According to the Vedic Brahmins one divine day was equal to one human year so that the period of Kali Yuga which was 1,000 years plus 200 years of Sandhya and Sandhamsa i.e. 1,200 years in all became (1200 × 360) equal to 4,32,000 years. In these two ways the Vedic Brahmins instead of declaring the end of Kali Yuga in 165 B.C. as the astronomer had said extended its life to 4,32,000 years. No wonder Kali Yuga continues even to-day and will continue for lakhs of years. There is no end to the Kali Yuga.

IV

What does the Kali Yuga stand for ? The Kali Yuga means an age of adharma, an age which is demoralized and an age in which the laws made by the King ought not to be obeyed. One question at once arises. Why was the Kali Yuga more demoralized than the preceding Yugas? What was the moral condition of the Aryans in the Yuga or Yugas preceding the present Kali Yuga? Anyone who compares the habits and social practices of the later Aryans with those of the ancient Aryans will find a tremendous improvement almost amounting to a social revolution in their manners and morals.

The religion of the Vedic Aryans was full of barbaric and obscene observances. Human sacrifice formed a part of their religion and was called Naramedhayagna. Most elaborate descriptions of the rite are found in the Yajur-Veda Samhita, Yajur-Veda Brahmanas, the Sankhyana and Vaitana Sutras. The worship of genitals or what is called Phallus worship was quite prevalent among the ancient Aryans. The cult of the phallus came to be known as Skambha and was recognized as part of Aryan religion as may be seen in the hymn in Atharva-Veda X.7. Another instance of obscenity which disfigured the religion of the Ancient Aryans is connected with the Ashvamedha Yajna or the horse sacrifice. A necessary part of the Ashvamedha was the introduction of the Sepas (penis) of the Medha (dead horse) into the Yoni (vagina) of the chief wife of the Yajamana (the sacrificer) accompanied by the recital of long series of Mantras by the Brahmin priests. A Mantra in the Vajasaneya Samhita (xxiii. 18) shows that there used to be a competition among the queens as to who was to receive this high honour of being served by the horse. Those who want to know more about it will find it in the commentary of Mahidhara on the Yejur-Veda where he gives full description of the details of this obscene rite which had formed a part of the Aryan religion.

The morals of the Ancient Aryans were no better than their religion. The Aryans were a race of gamblers. Gambling was developed by them into a science in very early days of the Aryan civilization so much so that they had even devised the dice and given them certain technical terms. The luckiest dice was called Krit and the unluckiest was called Kali. Treta and Dwapara were intermediate between them. Not only was gambling well developed among the ancient Aryans but they did not play without stakes. They gambled with such abandon that there is really no comparison with their spirit of gambling. Kingdoms and even wives were offered as stakes at gambling. King Nala staked his kingdom and lost it. The Pandvas went much beyond. They not only staked their kingdom but they also staked their wife, Draupadi, and lost both. Among the Aryans gambling was not the game of the rich. It was a vice of the many.

The ancient Aryans were also a race of drunkards. Wine formed a most essential part of their religion. The Vedic Gods drank wine. The divine wine was called Soma. Since the Gods of the Aryans drank wine the Aryans had no scruples in the matter of drinking. Indeed to drink it was a part of an Aryan’s religious duty. There were so many Soma sacrifices among the ancient Aryans that there were hardly any days when Soma was not drunk. Soma was restricted to only the three upper classes, namely, the Brahmins, the Kshatriyas and the Vaishyas. That does not mean the Shudras were abstainers. Those who were denied Soma drank Sura which was ordinary, unconsecrated wine sold in the market. Not only the Male Aryans were addicted to drinking but the females also indulged in drinking. The Kaushitaki Grihya Sutra .

I.11.12 advises that four or eight women who are not widowed after having been regaled with wine and food should be called to dance for four times on the night previous to the wedding ceremony. This habit of drinking intoxicating liquor was not confined to the Non-Brahmin women. Even Brahmin women were addicted to it. Drinking was not regarded as a sin. It was not even a vice, it was quite a respectable practice. The Rig-Veda says:

“Worshipping the Sun before drinking Madira (wine).”

The Yajur-Veda says:

“ Oh, Deva Soma! being strengthened and invigorated by Sura (wine), by thy pure spirit please the Devas; give juicy food to the sacrificer and vigour to Brahmanas and Kshatriyas.”

The Mantra Brahmana says:

“By which women have been made enjoyable by men, and by which water has been transformed into wine (for the enjoyment of men), etc.”

That Rama and Sita both drank wine is admitted by the Ramayana.

Utter Khand says:

“Like Indra in the case of (his wife) Shachi, Rama Chandra made Sita drink purified honey made wine. Servants brought for Rama Chandra meat and sweet fruits.”

So did Krishna and Arjuna. In the Udyoga Parva of the Mahabharat Sanjaya says:

“Arjuna and Shri Krishna drinking wine made from honey and being sweet-scented and garlanded, wearing splendid clothes and ornaments, sat on a golden throne studded with various jewels. I saw Shrikrishna’s feet on Arjuna’s lap, and Arjuna’s feet on Draupadi and Satyabhama’s lap.”

We may next proceed to consider the marital relations of men and women. What does history say? In the beginning there was no law of marriage among the Aryans. It was a state of complete promiscuity both in the higher and lower classes of the society. There was no such thing as a question of prohibited degrees as the following instances will show.

Brahma married his own daughter Satarupa. Their son was Manu the founder of the Pruthu dynasty which preceded the rise of the Aiksvakas and the Ailas.

Hiranyakashpu married his daughter Rohini. Other cases of father marrying daughters are Vashishtha and Shatrupa, Janhu and Jannhavi, and Surya and Usha. That such marriages between father and daughters were common is indicated by the usage of recognizing Kanin sons. Kanin sons mean sons born to unmarried daughter. They were in law the sons of the father of the girl. Obviously they must be sons begotten by the father on his own daughter

There are cases of father and son cohabiting with the same woman, Brahma is the father of Manu and Satarupa is his mother. This Satarupa is also the wife of Manu. Another case is that of Shradha. She is the wife of Vivasvat. Their son is Manu. But Shradha is also the wife of Manu thus indicating the practice of father and son sharing a woman. It was open for a person to marry his brother’s daughter. Dharma married 10 daughters of Daksha though Daksha and Dharma were brothers. One could also marry his uncle’s daughter as did Kasyapa who married 13 wives all of whom were the daughters of Daksha and Daksha was the brother of Kasyapa’s father Marichi.

The case of Yama and Yami mentioned in the Rig-Veda is a notorious case, which throws a great deal of light on the question of marriages between brothers and sisters. Because Yama refused to cohabit with Yami it must not be supposed that such marriages did not exist.

The Adi Parva of the Mahabharata gives a geneology which begins from Brahmadeva. According to this geneology Brahma had three sons Marichi, Daksha and Dharma and one daughter whose name the geneology unfortunately does not give. In this very geneology it is stated that Daksha married the daughter of Brahma who was his sister and had a vast number of daughters variously estimated as being between 50 and 60. Other instances of marriages between brothers and sisters could be cited. They are Pushan and his sister Acchoda and Amavasu. Purukutsa and Narmada, Viprachiti and Simhika, Nahusa and Viraja, Sukra-Usanas and Go, Amsumat and Yasoda, Dasaratha and Kausalya, Rama and Sita; Suka and Pivari; Draupadi and Prasti are all cases of brothers marrying sisters.

The following cases show that there was no prohibition against son cohabiting with his mother. There is the case of Pushan and his mother Manu and Satrupa and Manu and Shradha. Attention may also be drawn to two other cases, Arjuna and Urvashi and Arjuna and Uttara. Uttara was married to Abhimanyu son of Arjuna when he was barely 16. Uttara was associated with Arjuna. He taught her music and dancing. Uttara is described as being in love with Arjuna and the Mahabharata speaks of their getting married as a natural sequel to their love affair. The Mahabharata does not say that they were actually married but If they were, then Abhimanyu can be said to have married his mother. The Arjuna Urvasi episode is more positive in its indication.

Indra was the real father of Arjuna. Urvashi was the mistress of Indra and therefore in the position of a mother to Arjuna. She was a tutor to Arjuna and taught him music and dancing. Urvasi became enamoured of Arjuna and with the consent of his father, Indra, approached Arjuna for sexual intercourse. Arjuna refused to agree on the ground that she was like mother to him. Urvashi’s conduct has historically more significant than Arjuna’s denial and for two reasons. The very request by Urvashi to Arjuna and the consent by Indra show that Urvashi was following a well established practice. Secondly, Urvashi in her reply to Arjuna tells him in a pointed manner that this was a well recognized custom and that all Arjuna’s forefathers had accepted precisely similar invitations without any guilt being attached to them.

Nothing illustrates better than the complete disregard of consanguity in cohabitation in ancient India than the following story which is related in the second Adhyaya of the Harivamsha. According to it Soma was the son of ten fathers—suggesting the existence of Polyandry—each one of whom was called Pralheta. Soma had a daughter Marisha—The ten fathers of Soma and Soma himself cohabited with Marisha. This is a case of ten grand-fathers and father married to a woman who was a grand-daughter and daughter to her husbands. In the same Adhyaya the story of Daksha Prajapati is told. This Daksha Prajapati who is the son of Soma is said to have given his 27 daughters to his father, Soma for procreation. In the third Adhyaya of Harivamsha the author says that Daksha gave his daughter in marriage to his own father Brahma on whom Brahma begot a son who became famous as Narada. All these are cases of cohabitation of Sapinda men, with Sapinda women.

The ancient Aryan women were sold. The sale of daughters is evidenced by the Arsha form of marriage. According to the technical terms used the father of the boy gave Go-Mithuna and took the girl. This is another way of saying that the girl was sold for a Go-Mithuna. Go-Mithuna means one cow and one bull which was regarded as a reasonable price of a girl. Not only daughters were sold by their fathers but wives also were sold by their husbands. The Harivamsha in its 79th Adhyaya describes how a religious rite called Punyaka-Vrata should be the fee that should be offered to the officiating priest. It says that the wives of Brahmins should be purchased from their husbands and given to the officiating priest as his fee. It is quite obvious from this that Brahmins freely sold their wives for a consideration.

That the ancient Aryans let their women on rent for cohabitation to others is also a fact. In the Mahabharata there is an account of the life of Madhavi in Adhyayas 103 to 123. According to this account Madhavi was the daughter of King Yayati. Yayati made a gift of her to Galawa. Galva who was a Rishi as a fee to a priest. Galva rented her out to three kings in succession but to each for a period necessary to beget a son on her. After the tenancy of the third king terminated Madhavi was surrendered by Galva to his Guru Vishvamitra who made her his wife. Vishvamitra kept her till he begot a son on her and gave her back to Galva. Galva returned her to her father Yayati.

Polygamy and Polyandry were raging in the ancient Aryan society. The fact is so well known that it is unnecessary to record cases which show its existence. But what is probably not well known is the fact of promiscuity. Promiscuity in matters of sex becomes quite apparent if one were only to examine the rules of Niyoga which the Aryan name for a system under which a woman who is wedded can beget on herself a progeny from another who is not her husband. This system resulted in a complete state of promiscuity for it was uncontrolled. In the first place, there was no limit to the number of Niyogas open to a woman. Madhuti had one Niyoga allowed to her. Ambika had one actual Niyoga and another proposed. Saradandayani had three. Pandu allowed his wife Kunti four Niyogas. Vyusistasva was permitted to have 7 and Vali is known to have allowed as many as 17 Niyogas, 11 on one and 6 on his second wife. Just as there was no limit to the number of Niyogas so also there was no definition of cases in which Niyoga was permissible. Niyoga took place in the lifetime of the husband and even in cases where the husband was not overcome by any congenital incapacity to procreate. The initiative was probably taken by the wife. The choice of a man was left to her. She was free to find out with whom she would unite a Niyoga and how many times, if she chose the same man. The Niyogas were another name for illicit intercourse between men and women which might last for one night or twelve years or more with the husband a willing and a sleeping partner in this trade of fornication.

These were the manners and morals of common men in the ancient Aryan Society. What were the morals of the Brahmins ? Truth to tell they were no better men than those of the common men. The looseness of the morals among the Brahmins is evidenced by many instances. But a few will suffice. The cases showing that the Brahmins used to sell their wives has already been referred to. I will give other cases showing looseness. The Utanka is a pupil of Veda (the Purohita of Janmejaya III). The wife of Veda most calmly requests Utanka to take the place of her husband and ‘approach’ her for the sake of virtue. Another case that may be referred to in this connection is that of Uddalaka’s wife. She is free to go to other Brahmins either of her own free will, or in response to invitations. Shwetketu is her son by one of her husband’s pupils. These are not mere instances of laxity or adultery. These are cases of recognized latitudes allowed to Brahmin women. Jatila-Gautami was a Brahmin woman and had 7 husbands who were Rishis. The Mahabharata says that the wives of the citizens admire Draupadi in the company of her five husbands and compare her to Jatila Gautami with her seven husbands. Mamata is the wife of Utathya. But Brahaspati the brother of Utathya had free access to Mamata during the life time of Utathya. The only objection Mamata once raises to him is to ask him to wait on account of her pregnancy but does not say that approaches to her were either improper or unlawful.

Such immoralities were so common among the Brahmins that Draupadi when she was called a cow by Duryodhana for her polyandry is said to have said she was sorry that her husbands were not born as Brahmins.

Let us examine the morality of the rishis. What do we find?

The first thing we find is the prevalence of bestiality among the rishis. Take the case of the rishi called Vibhandaka. In Adhyaya 100 of the Vana Parva of the Mahabharata it is stated that he cohabited with a female deer and that the female deer bore a son to him who subsequently became known as Rishi Shranga. In Adhyaya 1 as well as in 118 of the Adi Parva of the Mahabharata there is a narration of how Pandu the father of the Pandavas received his curse from the Rishi by name Dama. Vyas says that the Rishi Dama was once engaged in the act of coitus with a female deer in a jungle. While so engaged Pandu shot him with an arrow before the rishi was spent as a result of it Dama died. But before he died Dama uttered a curse saying that if Pandu ever thought of approaching his wife he would die instantly. Vyas tries to gloss this bestiality of the rishi by saying that the Rishi and his wife had both taken the form of deer in fun and frolic. Other instances of such bestiality by the rishis it will not be difficult to find if a diligent search was made in the ancient religious literature in India.

Another heinous practice which is associated with the rishis is cohabitation with women in the open and within the sight of the public. In Adhyaya 63 of the Adi Parva of the Mahabharata a description is given of how the Rishi Parashara had sexual intercourse with Satyavati, alias Matsya Gandha a fisherman’s girl. Vyas says that he cohabited with her in the open and in public. Another similar instance is to be found in Adhyaya 104 of the Adi Parva. It is stated therein that the Rishi Dirgha Tama cohabited with a woman in the sight of the public. There are many such instances mentioned in the Mahabharata. There is, however, no need to encumber the record with them. For the word Ayonija is enough to prove the general existence of the practice. Most Hindus know that Sita, Draupadi and other renowned ladies are spoken of Ayonija. What they mean by Ayonija is a child born by immaculate conception. There is however no warrant from etymological point of view to give such a meaning to the Ayoni. The root meaning of the word Yoni is house. Yonija means a child born or conceived in the house. Ayonija means a child born or conceived outside the house. If this is the correct etymology of Ayonija it testifies to the practice of indulging in sexual intercourse in the open within the sight of the public.

Another practice which evidences the revolting immorality of the rishis in the Chandyogya Upanishad. According to this Upanishad it appears that the rishis had made a rule that if while they were engaged in performing a Yajna if a woman expressed a desire for sexual intercourse with the rishi who was approached should immediately without waiting for the completion of the Yajna and without caring to retire in a secluded spot proceeded to commit sexual intercourse with her in the Yajna Mandap and in the sight of the public. This immoral performance of the rishi was elevated to the position of a Religious observance and given the technical name of Vamadev- Vrata which was later on revived as Vama-Marga.

This does not exhaust all that one finds in the ancient sacredotal literature of the Aryans about the morality of the rishis. One phase of their moral life remains to be mentioned.

The ancient Aryans also seem to be possessed with the desire to have better progeny which they accomplished by sending their wives to others and it was mostly to the rishis who were regarded by the Aryas as pedigree cattle. The number of rishis who figure in such cases form quite a formidable number. Indeed the rishis seemed to have made a regular trade in this kind of immorality and they were so lucky that even kings asked them to impregnate the queens. Let us now take the Devas1.

The Devas were a powerful and most licentious community. They even molested the wives of the rishis. The story of how Indra raped Ahalya the wife of Rishi Gautama is well known. But the immoralities they committed on the Aryan women were unspeakable. The Devas as a community appears to have established an overlordship over the Aryan community in very early times. This overlordship had become degenerated that the Aryan women had to prostitute themselves to satisfy the lust of the Devas. The Aryans took pride if his wife was in the keeping of a Deva and was impregnated by him. The mention is in the Mahabharata and in the Harivamsha of sons born to Arya women from Indra, Yama, Nasatya, Agni, Vayu and other Devas is so frequent that one is astounded to note the scale on which such illicit intercourse between the Devas and the Arya women was going on.

In course of time the relations between the Devas and the Aryans became stablized and appears to have taken the form of feudalism. The Devas exacted two boons1 from the Aryans.

The first boon was the Yajna which were periodic feasts given by the Aryans to the Devas in return for the protection of the Devas in their fight against the Rakshasas, Daityas and Danavas. The Yajnas were nothing but feudal exactions of the Devas. If they have not been so understood it is largely because the word Deva instead of thought to be the name of a community is regarded as a term for expressing the idea of God which is quite wrong at any rate in the early stages of Aryan Society.

The second boon claimed by the Devas against the Aryans was the prior right to enjoy Aryan woman. This was systematized at a very early date. There is a mention of it in the Rig-Veda in X. 85.40. According to it the first right over an Arya female was that of Soma, second of Gandharva, third of Agni and lastly of the Aryan. Every Aryan woman was hypothecated to some Deva who had a right to enjoy her first on becoming puber. Before she could be married to an Aryan she had to be redeemed by getting the right of the Deva extinguished by making him a proper payment. The description of the marriage ceremony given in the 7th Khandika of the 1st Adhyaya of the Ashvalayan Grahya Sutra furnish the most cogent proof of the existence of the system. A careful and critical examination of the Sutra reveals that at the marriage three Devas were present. Aryaman, Varuna and Pushan, obviously because they had a right of prelibation over the bride. The first thing that the bride-groom does, is to bring her near a stone slab and make her stand on it telling her ‘Tread on this stone, like a stone be firm. Overcome the enemies; tread the foes down’. This means that the bridegroom does it to liberate the bride from the physical control of the three Devas whom he regards as his enemies. The Devas get angry and march on the bridegroom. The brother of the bride intervenes and tries to settle the dispute. He brings parched gram with a view to offer it the Angry Deva with a view to buy off their rights over the bride. The brother then asks the bride to join her palms and make a hollow. He then fills the hollow of her palm with the parched grain and pours clarified butter on it and asks her to offer it to each Deva three times. This offering is called Avadana. While the bride is making this Avadana to the Deva the brother of the bride utters a statement which is very significant. He says “This girl is making this Avadana to Aryaman Deva through Agni. Aryaman should therefore relinquish his right over the girl and should not disturb the possession of the bridegroom”. Separate Avadanas are made by the bride to the other two Devas and in their case also the brother alters the same formula. After the Avadan follows the Pradakshana round the Agni which is called SAPTAPADI after which the marriage of the bride and bridegroom becomes complete valid and good. All this of course is very illuminating and throw a flood of light on the utter subjection of the Aryans to the Devas and moral degradation of Devas as well as of the Aryans.

Lawyers know that Saptapadi is the most essential ceremony in a Hindu marriage and that without it there is no marriage at Law. But very few know why Saptapadi has so great an importance. The reason is quite obvious. It is a test whether the Deva who had his right of prelibation over the bride was satisfied with the Avadana and was prepared to release her. If the Deva allowed the bridegroom to take the bride away with him up to a distance covered by the Saptapadi it raised an irrebutable presumption that the Deva was satisfied with the compensation and that his right was extinguished and the girl was free to be the wife of another. The Saptapadi cannot have any other meaning. The fact that Saptapadi is necessary in every marriage shows how universally prevalent this kind of immorality had been among the Devas and the Aryans.

This survey cannot be complete without separate reference to the morals of Krishna. Since the beginning of Kali Yuga which is the same thing is associated with his death his morals became of considerable importance. How do the morals of Krishna compare with those of the others? Full details are given in another place about the sort of life Krishna led. To that I will add here a few. Krishna belonged to the Vrasni (Yadava family). The Yadavas were polygamous. The Yadava Kings are reported to have innumerable wives and innumerable sons— a stain from which Krishna himself was not free. But this Yadava family and Krishna’s own house was not free from the stain of parental incest. The case of a father marrying daughter is reported by the Matsya Purana to have occurred in the Yadav family. According to Matsya Purana, King Taittiri an ancestor of Krishna married his own daughter and begot-on her a son by name Nala. The case of a son cohabiting with his mother is found in the conduct of Samba the son of Krishna. The Matsya Purana tells how Samba lived an illicit life with the wives of Krishna his father and how Krishna got angry and cursed Samba and the guilty wives on that account. There is a reference to this in the Mahabharata also. Satyabhama asked Draupadi the secret of her power over her five husbands. According to the Mahabharata Draupadi warned her against talking or staying in private with her step-sons. This corroborates what the Matsya Purana has to say about Samba. Samba’s is not the only case. His brother Pradyumna married his foster mother Mayavati the wife of Sambara.

Such is the state of morals in the Aryan Society before the death of Krishna. It is not possible to divide this history into definite Yugas and to say that what state of morals existed in the Krita, what in Treta and what in Dwapara Yuga which closed at the death of Krishna If, however, we allow the ancient Aryans a spirit of progressive reform it is possible to say that the worst cases of immorality occurred in earliest age i.e. the Krita age, the less revolting in the Treta and the least revolting in the Dwapara and the best in the Kali age.

This line of thinking does not rest upon mere general development of human society as we see all over the world. That instead of undergoing a moral decay the ancient Aryan society was engaged in removing social evils by undertaking bold reforms is borne out by its history.

Devas and the rishis occupied a very high place in the eyes of the common Aryan and as is usual the inferior always imitate their superior. What the superior class does forms a standard for the inferior. The immoralities which were prevalent in the Aryan Society were largely the result of the imitation by the common man of the immoral acts and deeds of the Devas and the rishis. To stop the spread of immoralities in society the leaders of the Aryan Society introduced a reform of the greatest significance. They declared that acts and deeds of the Devas and the rishis are not to be cited1 or treated as precedents. In this way one cause and source of immorality was removed by a bold, and courageous stroke.

Other reforms were equally drastic. The Mahabharata refers to two reformers Dirghatama and Shwetaketu. It was laid down by Shwetketu that the marriage is indissoluble and there was to be no divorce. Two reforms are attributed to Dirghatama. He stopped polyandry and declared that a woman can have only one husband at a time. The second reform he is said to have carried out was to lay down conditions for regulating Niyog. The following were the most important of these conditions.

The father or brother of the widow (or of the widow’s husband) shall assemble the Gurus who taught or sacrificed for the deceased husband and his relatives and shall appoint her to raise issue for the deceased husband1.

(1) The husband, whether living or dead, must have no sons; (2) The Gurus in a family council should decide to appoint the widow to raise issue for her husband; (3) The person appointed must be either the husband’s brother or a sapinda, or sagotra of the husband or (according to Gautama) a sapravara or a person of the same caste. (4) The person appointed and the widow must be actuated by no lust but only by a sense of duty; (5) The person appointed must be anointed with ghee or oil (Narada Stripumsa, 82) must not speak with or kiss her or engage in the sportive dalliance with the women; (6) This relationship was to last till one son was born (or two according to some); (7) The widow must be comparatively young, she should not be old or sterile, or past child-bearing or sickly or unwilling or pregnant (Baud. Dh. S. II. 2.70, Narad, Stripumsa 83.84); (8) After the birth of a son they were to regard themselves as father-in-law and daughter- in-law (Manu IX, 62). It is further made clear by the texts that if a brother-in-law has intercourse with his sister-in-law without appointment by elders or if he does so even when appointed by elders but the other circumstances do not exist (e.g., if the husband has a son), he would be guilty of the sin of incest.”

There are other reforms carried out by the ancient Aryan Society necessary to improve its morals. One was to establish the rule of prohibited degrees for purposes of marriage to prevent recurrence of father-daughter, brother-sister, mother-son, grandfather-grand daughter marriages. The other was to declare sexual intercourse between the wife of the Guru and the pupil a heinous sin. Equally clear is the evidence in support of an attempt to control gambling. Every treatise in the series called Dharma Sutras contain references to laws made throwing on the King the duty and urgency of controlling gambling by State authorities under stringent laws.

All these reforms had taken effect long before the Kali Yuga started and it is natural to hold that from the point of view of morality the Kali Yuga was a better age. To call it an age in which morals were declining is not only without foundation but is an utter perversion.

This discussion about the Kali Yuga raised many riddles in the first place. How and when did the idea of mahayuga arise? It is true that all over the world the idea of a golden age lying in the past has been prevalent. But the idea of a Mahayuga is quite satisfied with the idea of a golden past prevelent elsewhere in India. Elsewhere the golden past is deemed to return. It is gone for ever. But in the idea of the Mahayuga the golden past is not gone for ever. It is to return after the cycle is complete.

The second riddle is why was the Kali Yuga not closed in 165 B.C. When according to the astronomer it was due to end why was it continued. Third riddle is the addition of Sandhya and Sandhyamsa periods to the Kali Yuga. It is quite obvious that these were later additions. For the Vishnu Purana states them separately. If they were original parts of Kali Yuga they would not have been stated separately why were these additions made. A fourth riddle is the change in the counting of the period. Originally the period of the Kali Yuga was said to be human years. Subsequently it was said to be a period of divine years with the result of the Kali Yuga being confined to 1200 years became extended to 4,32,000 years. That this was an innovation is quite obvious. For the Mahabharata knows nothing about this calculation in term of divine years. Why was this innovation made? What was the object of the Vedic Brahmins in thus indefinitely extending the period of the Kali Yuga? Was it to blackmail some Shudra Kings that the theory of Kali Yuga was invented and made unending so as to destroy his subjects from having any faith in his rule?

This Article is taken from Babasaheb Ambedkar’s book Riddles in Hinduism