The Units into which time is broken up for the purposes of reckoning it which are prevalent among the Hindus have not deserved the attention which their extraordinary character call for. This is a matter which forms one of the principal subject matter of the Puranas. There are according to the Puranas five measures of time (1) Varsha, (2) Yuga, (3) Maha Yuga, (4) Manwantara and (5) Kalpa. I will draw upon the Vishnu Purana to show what these units are.

To begin with the Varsha. This is how the Vishnu Purana explains it1 :

“Oh best of sages, fifteen twinklings of the eye make a Kashtha; thirty Kalas, one Muhurtta; thirty Muhurttas constitute a day and night of mortals : thirty such days make a month, divided into two half-months : six months form an Ayana (the period of the Sun’s progress north or south of the ecliptic): and two Ayanas compose a year.”

The same is explained in greater details at another place in the Vishnu Purana2.

“Fifteen twinklings of the eye (Nimedhas) make a Kashtha; thirty Kashthas, a Kala; Thirty Kalas, a Muhurtta (forty-eighty minutes); and thirty Muhurttas, a day and night; the portions of the day are longer or shorter, as has been explained; but the Sandhya is always the same in increase or decrease, being only one Muhurtta. From the period that a line may be drawn across the Sun (or that half his orb is visible) to the expiration of three Muhurttas (two hours and twenty-four minutes), that interval is called Pratar (morning), forming a fifth portion of the day. The next portion, or three Muhurttas from morning, is termed Sangava (forenoon): the three next Muhurttas constitute mid-day; the afternoon comprises the next three Muhurttas; the three Muhurttas following are considered as the evening; and the fifteen Muhurttas of the day are thus classed in five portions of three each.”

“Fifteen days of thirty Muhurttas each are called a Paksha (a lunar fortnight); two of these make a month; and two months, a solar season; three seasons a northern or southern declination (Ayana); and those two compose a year.”

The conception of Yuga is explained by the Vishnu Purana in the following terms1 :

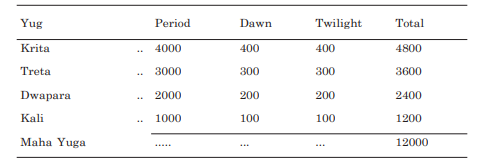

“Twelve thousand divine years, each composed of (three hundred and sixty) such days, constitute the period of the four Yugas, or ages. They are thus distributed : the Krita age has four thousand divine years; the Treta three thousand; the Dwapara two thousand; and Kali age one thousand; so those acquainted with antiquity have declared.

“The period that precedes a Yuga is called a Sandhya, and it is of as many hundred years as there are thousand in the Yuga; and the period that follows a Yuga, termed the Sandhyansa, is of similar duration. The interval between the Sandhya and the Sandhyasana is the Yuga, denominated, Krita, Treta, &c.”

The term Yuga is also used by the Vishnu Purana to denote a different measure of time. It says2 :

“Years, made up of four kinds of months, are distinguished into five kinds; and an aggregate of all the varieties of time is termed a Yuga, or cycle. The years are severally, called Samvatsara, Idvatsara, Anuvatsara, Parivatsara, and Vatsara. This is the time called a Yuga.”

The measure of Maha Yuga is an extension of the Yuga. As the Vishnu Purana points out3 :

“The Krita, Treta, Dwapara, and Kali constitute a great age, or aggregate of four ages : a thousand such aggregates are a day of Brahma.”

The Manwantara is explained by the Vishnu Purana in the following terms4 :

“The interval, called a Manwantara, is equal to seventy-one times, the number of years contained in the four Yugas, with some additional years.”

What is Kalpa is stated by the Vishnu Purana in the following brief text :

“Kalpa (or the day) of Brahma.”

These are the periods in which time is divided. The time included in these periods may next be noted.

The Varsha is simple enough. It is the same as the year or a period of 365 days. The Yuga, Maha Yuga, Manwantara and Kalpa are not so simple for calculating the periods. It would be easier to treat Yuga, Maha Yuga etc., as sub-divisions of a Kalpa rather than treat the Kalpa as a multiple of Yuga. Proceeding along that line the relation between a Kalpa and a Maha Yuga is that in one Kalpa there are 71 Maha Yugas while one Maha Yuga consists of four Yugas and a Manwantara is equal to 71 Maha Yugas with some additional years.

In computing the periods covered by these units we cannot take Yuga as our base for computation. For the Yuga is a fixed but not uniform period. The basis of computation is the Maha Yuga which consists of a fixed period.

A Maha Yuga consists of a period of four Yugas called (1) Krita, (2) Treta, (3) Dwapara and (4) Kali. Each Yuga has its period fixed. Each Yuga in addition to its period has a dawn and a twilight which have fixed-duration. Actual period as well as the period of the dawn and the twilight are different for the different Yugas.

This computation of the Maha Yuga is in terms of divine years i.e. 12000 divine years or years of Brahma make up one Maha Yuga at the rate of one year of men being equal to one divine day the Maha Yuga in terms of human or mortal years comes to (360 × 12000) 43,20,000 years.

Seventy-one Maha Yugas make one Kalpa. This means that a Kalpa is equal to (43,20,000 × 71) 3,06,72,000.

Coming to Manwantaras one Manvantara is equal to 71 Maha Yugas plus something more. The period of a manvantara is equal to that of a Kalpa i.e. 3,06,72,000 plus something more. The period of a Manvantara is bigger than the period included in a Kalpa.

The conception of a Varsha is in accord with astronomy and is necessary for the purpose of calculating time.

The conception of a Kalpa is both mythological and cosmological and is based upon the belief that the Universe undergoes the process of creation and dissolution; at the hands of Brahma and the period between creation and dissolution is called Kalpa. The first book of the Vishnu Purana is occupied with this. It begins with the details of creation. Creation is of twofold character, (1) primary (sarga) i.e. the origin of the universe from Prakriti or eternal crude matter; (2) Secondary (Pratisarga) i.e. the manner in which forms of things are developed from elementary substances previously evolved, or the manner in which they reappear after their temporary destruction. Both these creations are periodical, but the termination of the first occurs only at the end of the life of Brahma, when not only all the Gods and all other forms are annihilated, but the elements are again merged into primary substance, besides which one only spiritual being exists; the later takes place at the end of every Kalpa or day of Brahma, and affects only the forms of inferior creatures, and lower worlds, leaving the substance of the universe entire, and sages and Gods unharmed. Such is the conception underlying Kalpa.

The conception underlying Manvantara is mythological if not historical. It starts with the belief that Brahma gave rise to creation, inanimate as well as animate. But the animates did not multiply themselves. Brahma then created other 9 mind born sons but they were without desire or passion, inspired with holy, wisdom, estranged from the universe, and undesirous of progeny. Brahma having perceived this was filled with wrath. Brahma then converted himself into two persons, the first male, or Manu Swayambhuva and the first woman, or Satarupa. Manu Swayambhuva married Satarupa. Thus began the first Manvantara which is called Manvantara Swayambhuva. The fourteen Manvantaras are described as follows1

“Then, Brahma created himself the Manu Swayambhuva, born of, and identical with, his original self, for the protection of created beings, and the female portion of himself he constituted Satarupa, whom austerity purified from the sin (of forbidden nuptials), and whom the divine Manu Swayambhuva took to wife. From these two were born two sons, Priyavrata and Uttanapada, and two daughters, named Prasuti and Akuti graced with loveliness and exalted merit. Prasuti he gave to Daksha, after giving Akuti to the Patriarch Ruchi, who espoused her. Akuti bore to Ruchi twins, Yajna and Dakshina, who afterwards became husband and wife; and had twelve sons, the deities called Yamas, in the Manwantara of Swayambhuva.”

“1The first Manu was Swayambhuva, then came Swarochisha, the Auttami, then Tamasa, then Raivata, then Chakshusha : these six Manus have passed away. The Manu who presides over the seventh Manwantara, which is the present period, is Vaivaswata, the son of the Sun.”

“The period of Swayambhuva Manu, in the beginning of the Kalpa, has already been described by me, together with the gods, Rishis, and other personages, who then flourished. I will now, therefore, enumerate the presiding gods, Rishis, and sons of the Manu, in the Manwantara of Swarochisha. The deities of this period (or the second Manvantara) were the classes called Paravatas and Tushitas; and the king of the gods was the mighty Vipaschit. The seven Rishis were Urja, Stambha, Praria, Dattoli, Rishabha, Nischara, and Arvarivat; and Chaitra, Kimpurusha and others, were the Manu’s sons.

“In the third period, Or Manwantara of Auttami, Susanti was the Indra, the king of the gods the orders of whom were the Sudhamas, Satyas, Sivas, Pradersanas, and Vasavertis; each of the five orders consisting of twelve divinities. The seven sons of Vasishtha were the seven Rishis; and Aja, Parasu, Divya and others, were the sons of the Manu.

“The Surupas, Haris, Satyas, and Sudhis were the classes of gods, each comprising twenty-seven, in the period of Tamasa, the fourth Manu. Sivi was the Indra, also designated by his performance of a hundred sacrifices (or named Satakratu). The seven Rishis were Jyotirdhama, Prithu, Kavya, Chaitra, Agni, Vanaka, and Pivara. The sons of Tamasa were the mighty kings Nara, Khyati, Santahaya, Janujangha, and others.”

“In the fifth interval the Manu was Raivata; the Indra was vibhu : the classes of gods, consisting of fourteen each, were the Amitabhas, Abhutarajasas, Vaikunthas, and Sumedhasas; the seven Rishis were Hiranyaroma, Vedasri, Urdohabahu, Vedabahu, Sudhaman, Parjanya, and Mahamuni : the sons of Raivata were Balabandhu Susambhavya, Satyaka, and other valiant kings.”

“These four Manus, Swarochisha, Auttami, Tamasa, and Raivata, were all descended from Priyavrata, who in consequence of propitiating Vishnu by his devotions, obtained these rulers of the Manwantaras for his posterity.

“Chakshusha was the Manu of the sixth period in which the Indra was Janojava; the five classes of gods were the Adya,

Prastutas, Bhavyas, Prithugas, and the magnanimous Lekhas, eight of each : Sumedhas, Virajas, Havishmat, Uttama, Madhu, Abhinaman, and Sahishnu were the seven sages; the kings of the earth, the sons of Chakshusha, were the powerful Uru, Puru, Satadhumna, and others.”

“The Manu of the present is the wise lord of obsequies, the illustrious offspring of the sun; the deities are the Adityas, Vasus, and Rudras; their sovereign is Purandra : Vasistha, Kasyapa, Atri, Jamadagni, Gautama, Viswamitra, and Bharadwaja are the seven Rishis; and the nine pious sons of Vaivaswata Manu are the kings Ikshwaku, Nabhaga, Dhrishta, Sanyati, Narishyanata Nabhanidishta, Karusha, Prishadhra, and the celebrated Vasumat.”

So far the particulars of seven Manvantaras which are spoken of by the Vishnu Purana as the past Manwantaras. Below are given the particulars of other seven1 :

“Sanjana, the daughter of Viswakarman, was the wife of the Sun, and bore him three children, the Manu (Vaivaswata), Yama, and the goddess Yami (or the Yamuna river). Unable to endure the fervours of her lord, Sanjana gave him. Chhaya as his handmaid, and repaired to the forests to practise devout exercises. The Sun, supposing Chhaya to be his wife Sanjana, begot by her three other children, Sanaischara (Saturn), another Manu (Savarni), and a daughter Tapati (the Tapti river). Chhaya, upon one occasion, being offended with Yama, the son of Sanjana, denounced an imprecation upon him, and thereby revealed to Yama and to the Sun that she was not in truth Sanjana, the mother of the former. Being further informed by Chhaya that his wife had gone the wilderness, the Sun beheld her by the eye of meditation engaged in austerities, in the figure of a mare (in the region of Uttara Kuru). Metamorphosing himself into a horse, he rejoined his wife, and begot three other children, the two Aswins, and Revanta, and then brought Sanjana back to his own dwelling. To diminish his intensity, Viswakarman placed the luminary on his lathe to grind off some of his effulgence; and in this manner reduced it an eight, for more than that was inseparable. The parts of the divine Vaishnava slendour, residing in the Sun, that were filed off by Viswakarman, fell blazing down upon the earth, and the artist constructed of them the discuss of Vishnu, the trident of Siva, the weapon of the god of wealth, the lance of Kartikeya, and the weapons of the other gods : all these Viswakarman fabricated from the superfluous rays of the sun.

“The son of Chhaya, who was called also a Manu was denominated Savarni, from being of the same caste (Savarni) as his elder brother, the Manu Vaivaswata. He presides over the ensuing or eighth Manwantara; the particulars of which, and the following, I will now relate. In the period in which Savarni shall be the Manu, the classes of the gods will be Sutapas, Amitabhas, and Mukhyas; twentyone of each. The seven Rishis will be Diptimat, Galava, Rama, Kripa, Drauni; my son Vyasa will be the sixth, and the seventh will be Rishyasringa. The Indra will be Bali, the sinless son of Virochan who through the favour of Vishnu is actually sovereign of part of Patala. The royal progeny of Savarni will be Virajas, Arvariva, Nirmoha, and others.”

“The ninth Manu will be Daksha-Savarni. The Paras, Marichigarbhas, and Sudharmas will be the three classes of divinities, each consisting of twelve; their powerful chief will be the Indra, Abhuta. Savana, Dyutimat, Bhavya, Vasu, Medhatithi, Jyotishaman, and Satya will be the seven Rishis. Dhritketu, Driptiketu, Panchahasta, Niramaya, Prithusraya, and others will be the sons of the Manu.”

“In the tenth Manwantara the Manu will be Brahma-savarni; the gods will be the Sudhamas, Viruddhas, and Satasankhyas; the Indra will be the mighty Santi; the Rishis will be Havishaman, Sukriti, Satya, Appammurti, Nabhaga, Apratimaujas and Satyaketu; and the ten sons of the Manu will be Sukshetra, Uttamaujas, Harishena and others.”

“In the eleventh Manwantara the Manu will be Dharma-savarni; the principal classes of gods will be the Vihangama Kamagamas, and the Nirmanaratis, each thirty in number; of whom Vrisha will be the Indra : the Rishis will be Nischara, Agnitejas, Vapushaman, Vishnu, Aruni, Havishaman, and Anagha; the kings of the earth, and sons of the Manu, will be Savarga, Sarvadharma, Devanika, and others.”

“In the twelfth Manwantara the son of Rudra, Savarni, will be the Manu : Ritudhama will be the Indra; and the Haritas, Lohitas : Sumanasas, and Sukrmas will be the classes of gods, each comprising fifteen Tapaswi, Sutapas, Tapomurti, Taporati, Tapodhriti, Tapodyuti and Tapodhana will be the Rishis; and Devavan, Upadeva, Devasreshtha and others, will be the Manu’s sons, and mighty monarchs on the earth.”

“In the thirteenth Manwantara the Manu will be Rauchya; the classes of gods thirty-three in each will be the Sudhamanas, Sudharmans, and Sukarmanas, their Indra will be Divaspati; the Rishis will be Nirmoha, Tatwadersin, Nishprakampa, Nirutsuka, Dhritimat, Avyaya, and Sutapas; and Chitrasena, Vichitra, and others, will be the kings.”

“In the fourteenth Manwantara, Bhautya will be the Manu; Suchi, the Indra : the five classes of gods will be the Chakshushas, the Pavitras. Kanishthas, Bhrajiras, and Vavriddhas; the seven Rishis will be Agnibahu, Suchi, Sukra, Magadha, Gridhra, Yukta and Ajita; and the sons of the Manu will be Uru, Gabhira, Bradhna, and others, who will be kings, and will rule over the earth.”

The scheme of Manwantaras seems to be designed to provide a governing body for the universe during the period of a Manwantara. Over every Manwantara there presides a Manu as the legislator, Deities to worship, seven Rishis and a King to administer the affairs.

As the Vishnu Purana says1:

“The deities of the different classes receive the sacrifices during the Manwantaras to which they severally belong; and the sons of the Manu themselves, and their descendants, are the sovereigns of the earth for the whole of the same term. The Manu, the seven Rishis, the gods, the sons of the Manu, who are kings, and Indra, are the beings who preside over the world during each Manwantara.”

But the scheme of chronology called the Maha Yuga is a most perplexing business.

Why Kalpa should have been divided into Maha Yugas and why a Maha Yuga should have been sub-divided into four Yugas, Krita, Treta, Dwapara and Kali is a riddle which needs explanation. It is not based on mythology and unlike the era it has no reference to any real or supposed history of the Hindus.

In the first place why was the period covered by a Yuga so enormously extended as to make the whole chronoloy appear fabulous and fabricated

In the Rig-Veda the word Yuga occurs at least 38 times. It is used in the sense of age, generation, yoke or tribe. In a few places it appears to refer to a very brief period. In many places it appears to refer to a very brief period and Sayana even goes so far as to render the term yuge yuge by pratidinam i.e. every day.

In the next place the conception of four Yugas is associated with a deterioration in the moral fibre in society. This conception is well stated in the following extract from the Mahabharata2 :

“The Krita is that age in which righteousness is eternal. In the time of that most excellent of Yugas (everything) had been done (Krita) and nothing (remained) to be done. Duties did not then languish, nor did the people decline. Afterwards, through (the influence of) time, this yuga fell into a state of inferiority. In that age there were neither Gods, Danavas, Gahdharvas, Yakshas, Rakshasas, nor Pannagas; no buying or selling went on; the Vedas were not classed as Saman, Rich, and Yajush; no efforts were made by men: the fruit (of the earth was obtained) by their mere wish : righteousness and abandonment of the world (prevailed). No disease or decline of the organs of sense arose through the influence of the age; there was no malice, weeping, pride, or deceipt; no contention, and how could there be any lassitude ? No hatred, cruelty, fear affliction, jealousy, or envy. Hence the Supreme Brahma was the transcendent resort of those Yogins. Then Narayana the soul of all beings, was white, Brahmans, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas and Shudras possessed the characteristics of Krita. In that age were born creatures devoted to their duties. They were alike in the object of their trust, in observances and in their knowledge. At that period the castes, alike in their functions, fulfilled their duties, were unceasingly devoted to one deity, and used one formula (mantra), one rule and one rite. Though they had separate duties, they had but one Veda, and practised one duty. By works connected with the four orders, and dependent on conjunctures of time, but unaffected by desire, or (hope of) reward, they attained to supreme felicity. This complete and eternal righteousness of the four castes during the Krita was marked by the character of that age and sought after union with the supreme soul. The Krita age was free from the three qualities. Understand now the Treta, in which sacrifice commenced, righteousness decreased by a fourth, Vishnu became red; and men adhered to truth, and were devoted to a righteousness dependent on ceremonies. Then sacrifices prevailed, with holy acts and a variety of rites. In the Treta men acted with an object in view, seeking after reward for their rites and their fights, and no longer disposed to austerities and to liberality from (a simple feeling of) duty. In this age, however, they were devoted to their own duties, and to religious ceremonies. In the Dwapara age righteousness was diminished by two quarters, Vishnu became yellow, and the Veda fourfold. Some studied four Vedas, others three, others two, others one, and some none at all. The scriptures being thus divided, ceremonies were celebrated in a great variety of ways; and the people being occupied with austerity and the bestowal of gifts; became full of passion (rajasi). Owing to ignorance of the one Veda, Vedas were multiplied. And now from the decline of goodness (Sattva) few only adhered to truth. When men had fallen away from goodness, many diseases, desires and calamities, caused by destiny, assailed them, by which they were severely afflicted, and driven to practice austerities. Others desiring enjoyment and heavenly bliss, offered sacrifices. Thus, when they had reached the Dwapara, men declined through unrighteousness. In the Kali righteousness remained to the extent of one fourth only. Arrived in that age of darkness, Vishnu became black; practices enjoined by the Vedas, works of righteousness, and rites of sacrifice, ceased. Calamities, diseases, fatigue, faults, such as anger, etc., distresses, anxiety, hunger, fear, prevailed. As the ages revolve, righteousness again declines. When this takes places the people also decline. When they decay, the impulses which actuate them also decay. The practices generated by this declension of the Yugas frustrate men’s aims. Such is the Kali Yuga which has existed for a short time. Those who are long lived act in conformity with the character of the age.”

This is undoubtedly very strange. There is reference to these terms in the ancient vedic literature. The words Krita, Treta, Dwapara and Askanda occur in the Taittiriya Sanhita and in the Vajasaneyi Sanhita, in the Aiteriya Brahmana and also in the Satapatha Brahmana. The Satapatha Brahmana refers “to Krita as one who takes advantage of mistakes in the game; to the Treta as one who plays on a regular plan; to the Dwapara as one who plans to over reach his fellow player to Askanda a post of the gaming room”. In the Aiteriya Brahmana and the Taiteriya Brahmana the word Kali is used in place of Askanda. The Taiteriya Brahmana speaks of the Krita as the master of the gaming hall, to the Treta as one who takes advantage of mistakes, to the Dwapara as one who sits outside, to the Kali as one who is like a post of the gaming house i.e. never leaves it. The Aiteriya Brahmana says :

There is every success to be hoped; for the unluckiest die, the Kali is lying, two others are slowly moving and half fallen, but the luckiest, the Krita, is in full motion.” It is clear that in all these places the words have no other meaning than that of throws or dice in gambling.

The sense in which Manu uses these terms may also be noted.

He says1

“The Krita, Treta, Dwapara and Kaliyugas are all modes of a King’s action; for a King is called a Yuga; while asleep he is Kali; waking he is the Dwapra age; he is intent upon action he is Treta, moving about he is Krita.”

Comparing Manu with his predecessors one has to admit that a definite change in the connotation of these words have taken place-words which formed part of the gamblers jargon have become terms of Politics having reference to the readiness of the King to do his duty and making a distinction between various types of kings, those who are active, those who are intent on action, those who are awake and those who are sleeping

i.e. allowing society to go to dogs.

The question is what are the circumstances that forced the Brahmins to invent the theory of Kali Yuga ? Why did the Brahmins make Kali Yuga synonymous with the degraded state of Society ? Why Manu calls a sleeping ruler King Kali ? Who was the King ruling in Manu’s time ? Why does he call him a sleeping King ? These are some of the riddles which the theory of Kali Yuga gives rise to.

There are other riddles besides these which a close examination of the Kali Yuga theory presents us with. When does the Kali age actually commence ?

There are various theories about the precise date when the Kali Yuga began. The Puranas have given two dates. Some say that it commenced about the beginning of the XIV century B.C. Others say that it began on the 18th February 3102 B.C. a date on which the war between the Kauravas and Pandavas is alleged to have been found. As pointed out by Prof. Iyengar there is no evidence to prove that the Kali era was used earlier than the VII century A.D. anywhere in India. It occurs for the first time in an inscription belonging to the reign of Pulakeshi II who ruled at Badami between 610 and 642 A.D. It records two dates the Saka date 556 and the Kali date 3735. These dates adopt 3102 B.C. as the starting date of Kali Yuga. This is wrong. The date 3102 B.C. is neither the date of the Mahabharata war nor is the date of the commencement of the Kali Yuga. Mr. Kane has conclusively proved. According to the most positive statements regarding the king of different dynasties that have ruled from Parikshit the son of the Pandavas the precise date of the Mahabharata War was 1263 B.C. It cannot be 3102 B.C. Mr. Kane has also shown that the date 3102 B.C. stands for the beginning of the Kalpa and not for the beginning of Kali and that the linking up of Kali with the date 3102 B.C. instead of with the Kalpa was an error due to a misreading or a wrong transcription the term Kalpadi into Kalyadi. There is thus no precise date which the Brahmins can give for the commencement of the Kali Age. That there should be precise beginning which can be assigned to so remarkable an event is a riddle.

But there are other riddles which may be mentioned.

There are two dogmas associated with the Kali Age. It is strongly held by the Brahmans that in the Kali Age there are only two Varnas— the first and the last—the Brahmins and the Shudras. The two middle ones Kshatriyas and Vaishyas they say are non-existent. What is the basis of this dogma ? What does this dogma mean ? Does this mean that these Varnas were lost to Brahmanism or does this mean that they ceased to exist ?

Which is the period of India’s history which in fact accords with this dogma ? Does this mean that the loss of these two Varnas to Brahmanism marks the beginning of Kali Yuga ?

The second dogma associated with the theory of the Kali Yuga is called Kali Varjya—which means customs and usages which are not to be observed in the Kali Age. They are scattered in the different Puranas. But the Adityapurana has modified them and brought them in one place. The practices which come under Kali Varjya are given below1 :

To appoint the husband’s brother for procreating a son on a widow2.

“2. The remarriage of a (married) girl (whose marriage is not consummated) and of one (whose marriage was consummated) to another husband (after the death of the first).”3

- 4The marriage with girls of different Varna among persons of the three twice-born classes.”5

“4. 6The killing even in a straight fight of Brahmanas that have become desperadoes.7”

“5. The acceptance (for all ordinary intercourse such as eating with him) of a twice-born person who is in the habit of voyaging over the sea in a ship, even after he has undergone a prayascitta8.

“6. The initiation for a sattra.

“7. The taking a Kamandalu (a jar for water1)” “8. Starting on the Great Journey.”2

“9. The killing of a cow in the sacrifice called Gomedha;”3 “

10. The partaking of wine even in the Srautmani sacrifice.”4

11-12. Licking the ladle (sruc) after the Agnihotra Homa in order to take off the remains of the offerings and using the ladle, in the agnihotra afterwards when it has been so licked.”5

“13. Entering into the stage of forest hermit as laid down in sastras about it.”6 “14. Lessening the periods of impurity (due to death and birth) in accordance

with the conduct and vedic learning of a man.”7

“15. Prescribing death as the penance (Prayascitta) for Brahmanas.”8

“16. Explanation (by secretly performed Prayascittas) of the mortal sins other than theft (of gold) and the sin of contact (with those guilty of Mahapatakas).”9 “17. The act of offering with Mantras animal flesh to the bridegroom, the guest, and the pitrs.”10

“18. 1The acceptance as sons of those other than the aurasa

(natural) and adopted sons.”2

“19. Ordinary intercourse with those who incurred the sin of (having intercourse with) women of higher castes, even after they had undergone the Prayascitta for such sin.”3

“20. The abandonment of the wife of an elderly person (or of one who is entitled to respect) when she has had intercourse with one with whom it is severely condemned.”4

“21. 5‘Killing oneself for the sake of another.”6

“22. Giving up food left after one has partaken of it.”7

“23. Resolve to worship a particular idol for life (in return for payment)”8. “24. Touching the bodies of persons who are in impurity due to death

after the charred bones are collected”9.

“25. The actual slaughter by Brahmanas of the sacrificial animal.” “26. 10Sale of the Soma plant by Brahamanas.”11

“27. Securing food even from a Shudra when a Brahamana has had no food for six times of meals (i.e. for three days).”12

“28. Permission to (a Brahamana) householder to take cooked food from Shudras if they are his dasas, cowherds, hereditary friends, persons cultivating his land on an agreement to pay part of the produce.”13

“29. 1Going on a very distant pilgrimage.”

“30. Behaviour of a pupil towards his teacher’s wife as towards a teacher that is declared in smrtis”2.

“31. The maintenance by Brahamanas in adversity (by following unworthy avocations) and the mode of livelihood in which a Brahmana does not care to accumulate for tomorrow.”3

“32. 4The acceptance of aranis (two wooden blocks for producing fire) by Brahmanas (in the Homa at the time of jatakarma) in order that all the ceremonies for the child from jatakarma to his marriage may be performed therein.”5

“33. Constant journeys by Brahamanas.”

“34. Blowing of fire with the mouth (i.e. without employing a bamboo

dhamni.”6

“35. Allowing women who have become polluted by rape, &c, to freely mix in the caste (when they have performed prayascitta) as declared in the sastric texts.”7

“36. 8Begging of food by a sannayasin from persons of all Varnas (including sudra).”9

“37. To wait (i.e. not to use) for ten days water that has recently been dug in the ground.”

“38. Giving fee to the teacher as demanded by him (at the end of study) according to the rules laid down in the sastra.”10

“39. “The employment of sudras as cook for Brahmanas and the rest.”12 “40. Suicide of old people by calling from a precipice or into fire.”

“41. Performing Acamana by respectable people in water that would remain even after a cow has drunk it to its heart’s content.”1

“42. Fining witnesses who depose to a dispute between father and son.”12 “43. Sannyasin should stay where he happened to, be in the evening.”13 These are the Kali Varjyas set out in the adityapurana.

The strange thing about this code of Kali Varjya is that its significance has not been fully appreciated, it is simply referred to as a list of things forbidden in the Kali Yuga. But there is more than this behind this list of don’ts. People are no doubt forbidden to follow the practices listed in the Kali Varjya Code. The question however is : Are these practices condemned as being immoral, sinful or otherwise harmful to society ? The answer is no. One likes to know why these practices if they are forbidden are not condemned ? Herein lies the riddle of the Kali Varjya Code. This technique of forbidding a practice without condemning it stands in utter contrast with the procedure followed in earlier ages. To take only one illustration. The Apastamba Dharma Sutra forbids the practice of giving all property to the eldest son. But he condemns it. Why did the Brahmins invent this new technics forbid but not condemn ? There must be some special reason for this departure. What is that reason ?

This Article is taken from Babasaheb Ambedkar’s book Riddles in Hinduism