Mr. Mayne in his treatise on Hindu law has pointed out some anomalous features of the rules of Kinships. He says:

“No part of the Hindu Law is more anomalous than that which governs the family relations. Not only does there appear to be a complete break of continuity between the ancient system and that which now prevails, but the different parts of the ancient system appear in this respect to be in direct conflict with each other. We find a law of inheritance, which assumes the possibility of tracing male ancestors in an unbroken pedigre extending to fourteen generations; while coupled with it is a family law, in which several admitted forms of marriage are only euphemisms for seduction and rape, and in which twelve sorts of sons are recognized, the majority of whom have no blood relationship to their own father.”

The existence of this anomaly is a fact and will be quite clear to those who care to study the Hindu Law of marriage and paternity.

The Hindu Law recognizes eight different forms of marriage, namely

(1) Brahma, (2) Daiva, (3) Arsha, (4) Prajapatya, (5) Asura, (6) Gandharva, Rakshasa and (8) Paisacha.

The Brahma marriage is the gift of a daughter, clothed and decked to a man learned in the Veda, whom her father voluntarily invites and respectfully receives.

The Daiva marriage consists of the giving of the daughter by father to the family priest attending a sacrifice at the time of the payment of the sacrificial fee and in lieu of it.

Arsha marriage is characterized by the fact that the bridegroom has to pay a price for the bride to the father of the bride.

Prajapatya form of marriage is marked by the application of a man for a girl to be his wife and the granting of the application by the father of the girl. The difference between Prajapatya and Brahma marriage lies in the fact that in the latter the gift of the daughter is made by the father voluntarily but has to be applied for. The fifth or the Asura form of marriage is that in which the bridegroom having given as much wealth as he can afford to the father and paternal kinsmen and to the girl herself takes her as his wife. There is not much difference between Arsha and Asura forms of marriage. Both involve sale of the bride. The difference lies in this that in the Arsha form the price is fixed while in the Asura form it is not.

Gandharva marriage is a marriage by consent contracted from non- religious and sensual motives. Marriage by seizure of a maiden by force from her house while she weeps and calls for assistance after her kinsmen and friends have been slain in battle or wounded and their houses broken open, is the marriage styled Rakshasa.

Paisacha marriage is marriage by rape on a girl either when she is asleep or flushed with strong liquor or disordered in her intellect.

Hindu Law recognized thirteen kinds of sons. (1) Aurasa, (2) Kshetraja,

(3) Pautrikaputra, (4) Kanina, (5) Gudhaja, (6) Punarbhava, (7) Sahodhaja,

(8) Dattaka, (9) Kritrima, (10) Kritaka, (11) Apaviddha, (12) Svayamdatta

and (13) Nishada.

The Aurasa is a son begotten by a man himself upon his lawfully wedded wife.

Putrikaputra means a son born to a daughter. Its significance lies in the system under which a man who had a daughter but no son could also have his daughter to cohabit with a man selected or appointed by him. If a daughter gave birth to a son by such sexual intercourse the son became the son of the girl’s father. It was because of this that the son was called Putrikaputra. Man’s right to compel his daughter to submit to sexual intercourse with a man of his choice in order to get a son for himself continued to exist even after the daughter was married. That is why a man was warned not to marry a girl who had no brothers.

Kshetraja literally means son of the field i.e., of the wife. In Hindu ideology the wife is likened to the field and the husband being likened to the master of the field. Where the husband was dead, or alive but impotent or incurably diseased the brother or any other sapinda of the deceased was appointed by the family to procreate a son on the wife. The practice was called Niyoga and the son so begotten was called Kshetraja.

If an unmarried daughter living in the house of her father has through illicit intercourse given birth to a son and if she subsequently was married the son before marriage was claimed by her husband as his son. Such a son was called Kanina.

The Gudhaja was apparently a son born to a woman while the husband had access to her but it is suspected that he is born of an adulterous connection. As there is no proof by an irrebutable presumption so to say the husband is entitled to claim the son as his own. He is called Gudhaja because his birth is clouded in suspicious, Gudha meaning suspicion.

Sahodhaja is a son born to a woman who was pregnant at the time of her marriage. It is not certain whether he is the son of the husband who had access to the mother before marriage or whether it is the case of a son begotten by a person other than the husband. But it is certain that the Sahodhaja, is a son born to a pregnant maiden and claimed as his son by the man who marries her.

Punarbhava is the son of a woman who abandoned by her husband and having lived with others, re-enters his family. It is also used to denote the son of a woman who leaves an impotent, outcaste, or a mad or diceased husband and takes another husband.

Parasava1 is the son of a Brahmin by his Shudra wife.

The rest of the sons are adopted sons as distinguished for those who were claimed as sons.

Dattaka is the son whom his father and mother give in adoption to another whose son he then becomes.

Kratrima is a son adopted with the adoptee’s consent only.

Krita is a son purchased from his parents.

Apaviddha is a boy abandoned by his parents and is then taken in adopted and reckoned as a son.

Svayamdatta is a boy bereft of parents or abandoned by them seeks a man shelter and presents himself saying ‘Let me become thy son’ when accepted he becomes his son.

It will be noticed how true it is to say that many forms of marriage are only euphemisms for seduction and rape and how many of the sons have no blood relationship to their father. These different forms of marriage and different kinds of sons were recognized as lawful even up to the time of Mana and even the changes made by Manu are very minor. With regard to the forms of marriage Manu2 does not declare them to be illegal. All that he says that of the eight forms, six, namely, Brahma, Daiva, Arsha, Prajapatya, Asura, Gandharva, Rakshasa and Paisachya are lawful for a Kshatriya, and that three namely Asura, Gandharva and Paisachya are lawful for a Vaishya and a Shudra.

Similarly he does not disaffiliate any of the 12 sons. On the contrary he recognises their kinship. The only change he makes is to alter the rules of inheritance by putting them into two classes (1) heirs and kinsmen and (2) kinsmen but not heirs. He says1 :

- “The legitimate son of the body, the son begotten on a wife, the son adopted, the son made, the son secretly born, and the son cast off (are) the six heirs and kinsmen.”

- “The son of an unmarried damsel, the son received with the wife, the son bought, the son begotten on a remarried woman; the son self-given and the son of a Sudra female (are) the six (who are) not heirs, (but) kinsmen.”

- “If the two heirs of one man be a legitimate son of his body and a son begotten on his wife, each (of the two sons), to the exclusion of the other, shall take the estate of his (natural) father.”

- “The legitimate son of the body alone (shall be) the owner of the paternal estate; but, in order to avoid harshness, let him allow a maintenance to the rest.”

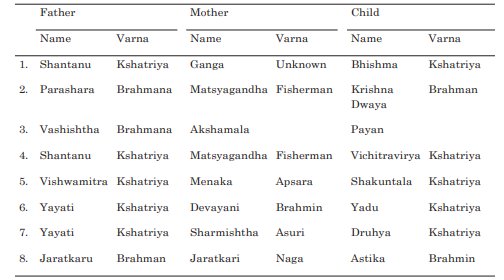

There is another part of the law of consanguinity which has undergone a profound change but which has hardly been noticed by anybody. It relates to the determination of the Varna of the child. What is to be the Varna of the child? Is it to be the father’s Varna or the mother’s Varna? According to the law as it prevailed in the days before Manu the Varna of the child was determined by the Varna of the father. The Varna of the mother was of no account. A few illustrations will suffice to prove the thesis.

What does Manu do? The changes made by Manu in the law of the child’s Varna are of a most revolutionary character. Manu1 lays down the following rules:

- “In all castes (varna) those (children) only which are begotten in the direct order on wedded wives, equal (in caste) and married as (virgins) are to be considered as belonging to the same caste (as their fathers).”

- “ Sons, begotten by twice-born men on wives of the next lower castes, they declare to be similar (to their fathers, but) blamed on account of the fault (inherent) in their mothers.”

- “Those sons of the twice-born, begotten on wives of the next lower castes, who have been enumerated in due order, they call by the name Anantaras (belonging to the next lower caste) on account of the blemish (inherent) in their mothers”

- “Six sons, begotten (by Aryans) on women of equal and the next lower castes (Anantara), have the duties of twice-born men; but all those born in consequence of a violation of the law are, as regards their duties, equal to Sudras.”

Manu distinguishes the following cases:

- Where the father and mother belong to the same Varna.

- Where the mother belongs to a Varna next lower to that of the father e.g., Brahman father and Kshatriya mother, Kshatriya father and Vaishya mother, Vaishya father and Shudra mother.

- Where the mother belongs to a Varna more than one degree lower to that of the father, e.g., Brahmin father and Vaishya or Shudra mother, Kshatriya father and Shudra mother.

In the first case the Varna of the child is to be the Varna of the father. In the second case also the Varna of the child is to be the Varna of the father. But in the third case the child is not to have the father’s Varna. Manu does not expressly say what is to be the Varna of the child if it is not to be that of the father. But all the commentators of Manu Medhatithi, Kalluka Bhatt, Narada and Nandapandit—agree

saying what of the course is obvious that in such cases the Varna of the child shall be the Varna of the mother. In short Manu altered the law of the child’s Varna from that of Pitrasavarna—according to father’s Varna to Matrasavarna—according to mother’s Varna.

This is most revolutionary change. It is a pity few have realized that given the forms of marriage, kinds of sons, the permissibility of Anuloma marriages and the theory of Pitrasavarnya, the Varna system notwithstanding the desire of the Brahmins to make it a closed system remained an open system. There were so many holes so to say in the Varna system. Some of the forms of marriage had no relation to the theory of the Varna. Indeed they could not have. The Rakshas and the Paisachya marriages were in all probability marriages in which the males belonged to the lower varnas and the females to the higher varnas. The law of sonship probably left many loopholes for the sons of Shudra to pass as children of the Brahmin. Take for instances sons such as Gudhajas, Sahodhajas, Kanina. Who can say that they were not begotten by Shudra or Brahmin, Kshatriya or Vaishya. Whatever doubts there may be about these the Anuloma system of marriage which was sanctioned by law combined with the law of Pitrasavarnya had the positive effect of keeping the Varna system of allowing the lower Varnas to pass into the higher Varna. A Shudra could not become a Brahmin, a Kshatriya or a Vaishya. But the child of a Shudra woman could become a Vaishya if she was married to a Vaishya, a Kshatriya if she was married to a Kshatriya and even a Brahmin if she was married to a Brahmin. The elevation and the incorporation of the lower orders into the higher orders was positive and certain though the way of doing it was indirect. This was one result of the old system. The other result was that a community of a Varna was always a mixed and a composite community. A Brahmin community might conceivably consist of children born of Brahmin women, Kshatriya women, Vaishya women, and Shudra women all entitled to the rights and privileges belonging to the Brahmin community. A Kshatriya community may conceivably consist of children born of Kshatriya women, Vaishya women and Shudra women all recognized as Kshatriya and entitled to the rights and privileges of the Kshatriya community. Similarly the Vaishya community may conceivably consist of children born of Vaishya women and Shudra women all recognized as Vaishyas and entitled to the rights and privileges of the Vaishya community.

The change made by Manu is opposed to some of the most fundamental notions of Hindu Law. In the first place, it is opposed to the Kshetra-Kshetraja rule of Hindu Law. According to this rule, which deals with the question of property in a child says that the owner of the child is the de jure husband of the mother and not the de facto father of the child. Manu is aware of this theory. He puts it in the following terms1:

“Thus men who have no marital property in women, but sow in the fields owned by others, may raise up fruit to the husbands, but the procreator can have no advantage from it. Unless there be a special agreement between the owners of the land and of the seed the fruit belongs clearly to the landowner, for the receptacle is more important than the seed.”

It is on this that the right to the 12 kinds of sons is founded.

This change was also opposed to the rule of Patna Potestas. Hindu family is a Patriarchal family same as the Roman family. In both the father possessed certain authority over members of the family. Manu is aware of this and recognized it in most ample terms. Defining the authority of the Hindu father, Manu says:

“Three persons, a wife, a son, and a slave, are declared by law to have in general no wealth exclusively their own; the wealth which they may earn is regularly acquired for the man to whom they belong.”

They belong to the head of the family—namely the father. Under the Patna Potestas the sons earnings are the property of the father. The change in the law of paternity mean a definite loss to the father.

Why did Manu change the law from Pitra-savarnya to Matra-savarnya ?

This Article is taken from Babasaheb Ambedkar’s book Riddles in Hinduism