There are various forms of Government known to history—Monarchy, Aristocracy and Democracy to which may be added Dictatorship.

The most prevalent form of Government at the present time is Democracy. There is however no unanimity as to what constitutes Democracy. When one examines the question one finds that there are two views about it. One view is that Democracy is a form of Government. According to this view where the Government is chosen by the people that is where Government is a representative Government there is Democracy. According to this view Democracy is just synonymous with Representative Government which means adult suffrage and periodical elections.

According to another view a democracy is more than a form of Government. It is a form of the organization of Society. There are two essential conditions which characterize a democratically constituted society. First is the absence of stratification of society into classes. The Second is a social habit on the part of individuals and groups which is ready for continuous readjustment or recognition of reciprocity of interests. As to the first there can be no doubt that it is the most essential condition of Democracy. As Prof. Dewey1 has observed:

[Quotation referred to by the author is not recorded in the original MS from ‘Democracy and Education’, by Dewey p. 98.]

The second condition is equally necessary for a democratically constituted society. The results of this lack of reciprocity of interests among groups and individuals produce anti-democratic results which have been well described by Prof. Dewey1 when he says:

[Quotation from ‘Democracy and Education’ of page 99 referred to by the author is not recorded in the original MS.]

Of the two views about democracy there is no doubt that the first one is very superficial if not erroneous. There cannot be democratic Government unless the society for which it functions is democratic in its form and structure. Those who hold that democracy need be no more than a mere matter of elections seem to make three mistakes.

One mistake they make is to believe that Government is something which is quite distinct and separate from society. As a matter of fact Government is not something which is distinct and separate from Society. Government is one of the many institutions which Society rears and to which it assigns the function of carrying out some of the duties which are necessary for collective social life.

The Second mistake they make lies in their failure to realize that a Government is to reflect the ultimate purposes, aims, objects and wishes of society and this can happen only where the society in which the Government is rooted is democratic. If society is not democratic, Government can never be. Where society is divided into two classes governing and the governed the Government is bound to be the Government of the governing class.

The third mistake they make is to forget that whether Government would be good or bad democratic or undemocratic depends to a large extent up on the instrumentalities particularly the Civil Service on which every where Government has to depend for administering the Law. It all depends upon the social milieu in which civil servants are nurtured. If the social milieu is undemocratic the Government is bound to be undemocratic.

There is one other mistake which is responsible for the view that for democracy to function it is enough to have a democratic form of Government. To realize this mistake it is necessary to have some idea of what is meant by good Government.

Good Government means good laws and good administration. This is the essence of good Government. Nothing else can be. Now there cannot be good Government in this sense if those who are invested with ruling power seek the advantage of their own class instead of the advantage of the whole people or of those who are downtrodden.

Whether the Democratic form of Government will result in good will depend upon the disposition of the individuals composing society. If the mental disposition of the individuals is democratic then the democratic form of Government can be expected to result in good Government. If not, democratic form of Government may easily become a dangerous form of Government. If the individuals in a society are separated into classes and the classes are isolated from one another and each individual feels that his loyalty to his class must come before his loyalty to every thing else and living in class compartments he becomes class conscious bound to place the interests of his class above the interests of others, uses his authority to pervert law and justice to promote the interests, of his class and for this purpose practises systematically discrimination against persons who do not belong to his caste in every sphere of life what can a democratic Government do. In a Society where classes clash and are charged with anti-social feelings and spirit of aggressiveness, the Government can hardly discharge its task of governing with justice and fairplay. In such a society, Government even though it may in form be a government of the people and by the people it can never be a Government for the people. It will be a Government by a class for a class. A Government for the people can be had only where the attitude of each individual is democratic which means that each individual is prepared to treat every other individual as his equal and is prepared to give him the same liberty which he claims for himself. This democratic attitude of mind is the result of socialization of the individual in a democratic society. Democratic society is therefore a prerequisite of a democratic Government. Democratic Governments have toppled down in largely due to the fact that the society for which they were set up was not democratic.

Unfortunately to what extent the task of good Government depends upon the mental and moral disposition of its subjects has seldom been realized. Democracy is more than a political machine. It is even more than a social system. It is an attitude of mind or a philosophy of life.

Some equate Democracy with equality and liberty. Equality and liberty are no doubt the deepest concern of Democracy. But the more important question is what sustains equality and liberty? Some would say that it is the law of the state which sustains equality and liberty. This is not a true answer. What sustains equality and liberty is fellow-felling. What the French Revolutionists called fraternity. The word fraternity is not an adequate expression. The proper term is what the Buddha called, Maitree. Without Fraternity Liberty would destroy equality and equality would destroy liberty. If in Democracy liberty does not destroy equality and equality does not destroy liberty, it is because at the basis of both there is fraternity. Fraternity is therefore the root of Democracy.

The foregoing discussion is merely a preliminary to the main question. That question is—wherein lie the roots of fraternity without which Democracy is not possible? Beyond dispute, it has its origin in Religion.

In examining the possibilities of the origin of Democracy or its functioning successfully one must go to the Religion of the people and ask—does it teach fraternity or does it not? If it does, the chances for a democratic Government are great. If it does not, the chances are poor. Of course other factors may affect the possibilities. But if fraternity is not there, there is nothing to built democracy on. Why did Democracy not grow in India? That is the main question. The answer is quite simple. The Hindu Religion does not teach fraternity. Instead it teaches division of society into classes or varnas and the maintenance of separate class consciousness. In such a system where is the room for Democracy ?

The Hindu social system is undemocratic not by accident. It is designed to be undemocratic. Its division of society into varnas and castes, and of castes and outcastes are not theories but are decrees. They are all barricades raised against democracy.

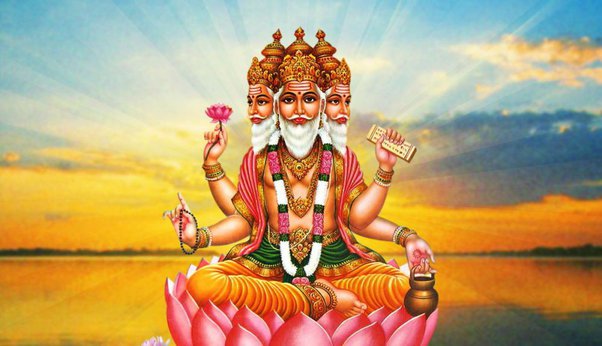

From this it would appear that the doctrine of fraternity was unknown to the Hindu Religious and Philosophic thought. But such a conclusion would not be warranted by the facts of history. The Hindu Religious and Philosophic thought gave rise to an idea which had greater potentialities for producing social democracy than the idea of fraternity. It is the doctrine of Brahmaism1.

It would not be surprising if some one asked what is this Brahmaism? It is something new even to Hindus. The Hindus are familiar with Vedanta. They are familar with Brahmanism. But they are certainly not familiar with Brahmaism. Before proceeding further a few words of explanation are necessary.

There are three strands in the philosophic and religious thought of the Hindus. They may be designated as (1) Brahmaism (2) Vedanta and (3) Brahmanism. Although they are correlated they stand for three different and distinct ideologies.

The essence of Brahmaism is summed up in a dogma which is stated in three different forms. They are—

- Sarvam Khalvidam Brahma—All this is Brahma.

- Aham Brahmasmi—Atmana (Self) is the same as Brahma. Therefore I am Brahma.

- Tattvamasi—Atmana (Self) is the same as Brahma. Therefore thou art also Brahma.

They are called Mahavakyas which means Great Sayings and they sum up the essence of Brahmaism.

The following are the dogmas which sum up the teachings of Vedant— I Brahma is the only reality.

- The world is maya or unreal.

- Jiva and Brahma are—

- according to one school identical;

- according to another not identical but are elements of him and not separate from him;

- according to the third school they are distinct and separate. The creed of Bramhanism may be summed up in the following dogmas—

- Belief in the chaturvarna.

- Sanctity and infallibility of the Vedas.

- Sacrifices to Gods the only way to salvation.

Most people know the distinction between the Vedanta and Brahmanism and the points of controversy between them. But very few people know the distinction between Brahmaism and Vedanta. Even Hindus are not aware of the doctrine of Brahmaism and the distinction between it and Vedanta. But the distinction is obvious. While Brahmaism and Vedanta agree that Atman is the same as Brahma. But the two differ in that Brahmaism does not treat the world as unreal, Vedanta does. This is the fundamental difference between the two.

The essence of Brahmaism is that the world is real and the reality behind the world is Brahma. Everything therefore is of the essence of Brahma.

There are two criticisms which have been levelled against Brahmaism. It is said that Brahmaism is piece of impudence. For a man to say “I am Brahma” is a kind of arrogance. The other criticism levelled against Brahmaism is the inability of man to know Brahma. ‘I am Brahma’ may appear to be impudence. But it can also be an assertion of one’s own worth. In a world where humanity suffers so much from an inferiority complex such an assertion on the part of man is to be welcomed. Democracy demands that each individual shall have every opportunity for realizing its worth. It also requires that each individual shall know that he is as good as everybody else. Those who sneer at Aham Brahmasmi (I am Brahma) as an impudent utterance forget the other part of the Maha Vakya namely Tatvamasi (Thou art also Brahma). If Aham Brahmasmi has stood alone without the conjunct of Tatvamasi it may not have been possible to sneer at it. But with the conjunct of Tatvanmsi the charge of selfish arrogance cannot stand against Brahmaism.

It may well be that Brahma is unknowable. But all the same this theory of Brahma has certain social implications which have a tremendous value as a foundation for Democracy. If all persons are parts of Brahma then all are equal and all must enjoy the same liberty which is what Democracy means. Looked at from this point of view Brahma may be unknowable. But there cannot be slightest doubt that no doctrine could furnish a stronger foundation for Democracy than the doctrine of Brahma.

To support Democracy because we are all children of God is a very weak foundation for Democracy to rest on. That is why Democracy is so shaky wherever it made to rest on such a foundation. But to recognize and realize that you and I are parts of the same cosmic principle leaves room for no other theory of associated life except democracy. It does not merely preach Democracy. It makes democracy an obligation of one and all.

Western students of Democracy have spread the belief that Democracy has stemmed either from Christianity or from Plato and that there is no other source of inspiration for democracy. If they had known that India too had developed the doctrine of Brahmaism which furnishes a better foundation for Democracy they would not have been so dogmatic. India too must be admitted to have a contribution towards a theoretical foundation for Democracy.

The question is what happened to this doctrine of Brahmaism ? It is quite obvious that Brahmaism had no social effects. It was not made the basis of Dharma. When asked why this happened the answer is that Brahmaism is only philosophy, as though philosophy arises not out of social life but out of nothing and for nothing. Philosophy is no purely theoretic matter. It has practical potentialities. Philosophy has its roots in the problems of life and whatever theories philosophy propounds must return to society as instruments of re-constructing society. It is not enough to know. Those who know must endeavour to fulfil.

Why then Brahmaism failed to produce a new society? This is a great riddle. It is not that the Brahmins did not recognize the doctrine of Brahmaism. They did. But they did not ask how they could support inequality between the Brahmin and the Shudra, between man and woman, between casteman and outcaste ? But they did not. The result is that we have on the one hand the most democratic principle of Brahmaism and on the other hand a society infested with castes, sub-outcastes, primitive tribes and criminal tribes. Can there be a greater dilemma than this ? What is more ridiculous is the teaching of the Great Shankaracharya. For it was this Shankarcharya who taught that there is Brahma and this Brahma is real and that it pervades all and at the same time upheld all the inequities of the Brahmanic society. Only a lunatic could be happy with being the propounder of two such contradictions. Truely as the Brahmin is like a cow, he can eat anything and everything as the cow does and remain a Brahmin.

This Article is taken from Babasaheb Ambedkar’s book Riddles in Hinduism