“I felt I was in heaven,” gushes Poorna Malavath over a video call from the US where she is studying. Her broad, toothy smile momentarily disappears. She chokes but doesn’t give in to tears.

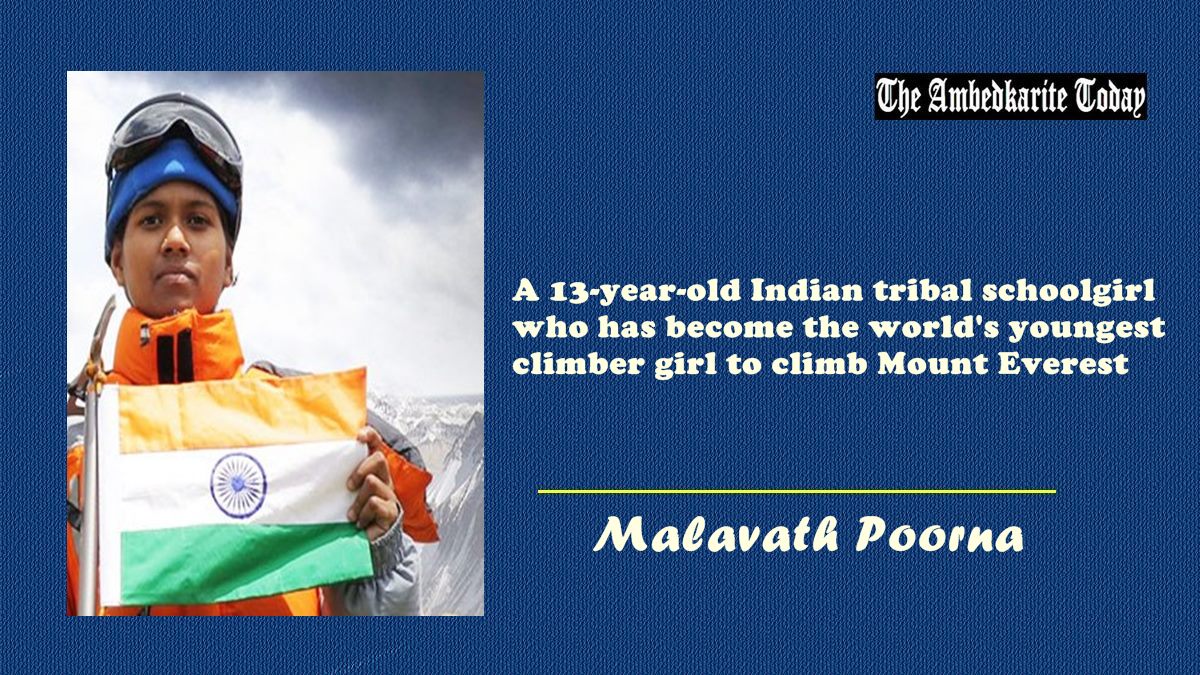

The 19-year-old was recalling the time she scaled Mount Everest in the summer of 2014, making history as the youngest person to ever do so at 13 years and 10 months. “I didn’t know it was a world record then,” she says sheepishly. But celebrate her victory she did, by making a satellite call to her mentor RS Praveen Kumar from the peak. “I told him I made it. He was so happy… I was so happy. No words can describe that feeling,” she says.

Their relationship dates back to the time when Malavath, aged 11, left her village in Pakala, northern Telangana, to join a residential school in a nearby district. A year or so later in 2012, Kumar, an IPS officer, was posted at the school. “He was keen on improving the quality of education in government schools,” says Malavath, whose parents, both agricultural workers, grow paddy on their 2-acre plot of land.

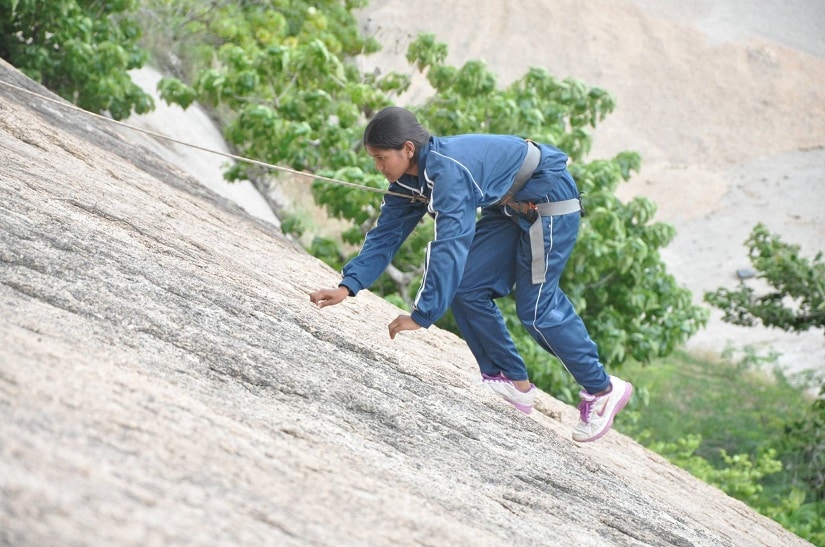

Early into his job Kumar found that despite his best efforts, the school dropout rate wasn’t improving. So he decided to implement extracurricular activities, notably rock climbing, in an attempt to retain students. On a whim, Malavath signed up and before long she was selected as one among 110 students from government-run schools across Telangana to go on a five-day excursion to Bhongir, a local rock-climbing mecca.

“When I stood in front of the rock that they wanted us to climb [around 6,500 feet], I was in shock. I thought, ‘Are they mad? Why did they bring us here?’” she laughs. “But nothing is impossible.”

Sure enough, at the end of the five days, having learnt the basics of balancing, bouldering and rappelling, Malavath stood first.

On coach Shekhar Babu’s suggestion, Kumar got permission to continue the children’s rock climbing endeavours; 26 of the 110 students were selected to go for further training to Darjeeling for a period of three months. Malavath was one of them. There too she shone. “Through the course of training, we noticed that Poorna is a very strong girl and can adapt to any situation. She has a never-give-up attitude,” says Babu.

Back in their home state, 13 of the 26 students were shortlisted for further training. During this time, Kumar set his sights on an Everest expedition for Malavath and Anand Kumar, the two star climbers in the group. Babu put the duo through six months of hard training that included running 20 to 25 km every day, volleyball playoffs and yoga sessions. Over the weekends, they would travel to Bhongir to put their rock-climbing prowess to practice. “We would train for about 5 to 6 hours daily and get only one day of rest a week,” says Malavath. Some days were tough, she concedes, but the best way against long odds, she says, is to “keep moving… never give up”.

She speaks with the kind of wisdom that usually comes with age. Consider another truth she figured out: “Intention without discipline is useless,” she says when asked about the gruelling schedule. Babu still trains Malavath albeit via WhatsApp as she is currently pursuing an exchange programme at the University of Minnesota.

Since her Mt Everest expedition, Malavath has conquered six of the highest peaks in each of the seven continents. The last one, Mt Denali is in Alaska and relatively close to where she is studying. “I hope I can climb it before I leave [in August],” she says.

But that depends on the monies available to her. While the state government sponsored Malavath’s journey to Mt Everest, Kumar and Babu sourced funds from other donors for her other feats. “Whenever I ask them, ‘Where did the money come from?’, they tell me, ‘You don’t worry about that. Just focus on climbing’,” she says.

Malavath’s Mt Everest feat inspired actor Rahul Bose to make a film on her. Titled Poorna (2017), the film showed how mountaineering wasn’t a choice for Malavath. It was the only option. It was an escape from getting married off early like most girls in her village. “The film is 80 percent true,” says Malavath. “It’s true that most girls in my village got married when they were young, but my parents, although uneducated, were aware. They wanted me to get an education first.”

“She was not only athletic but determined. She had that combination of physical strength and mental tenacity.”

Even crazier than ‘how’ Malavath conquered the world’s highest peak as a young teen is her ‘why’ behind it. Growing up in patriarchal Pakala, Malavath saw how her friends were forced to marry early, bear children and give up on their dreams. “It’s always thought that girls can’t do what boys do. I wanted to prove that wrong. If girls don’t get married early, we can do anything,” she says.

Now a role model for those in her village and beyond, Malavath seems to have achieved that. But she’s not done yet. Once she returns home, she plans to pursue her postgraduate studies, clear the Civil Services Exam and join the Indian Police Service, just like Kumar.

“Government schools in Telangana are now as good as private schools; that’s all because of Praveen Sir. Because of him my life has completely changed. I too want to give back to society,” she says.

Does she credit her maturity to mountaineering? “I don’t know,” she shrugs coyly. Then again one is reminded that she’s just 19.

Editors Note – This story appears in the 13 March, 2020 issue of Forbes India, written by VARSHA MEGHANI Journalist at Forbes India.