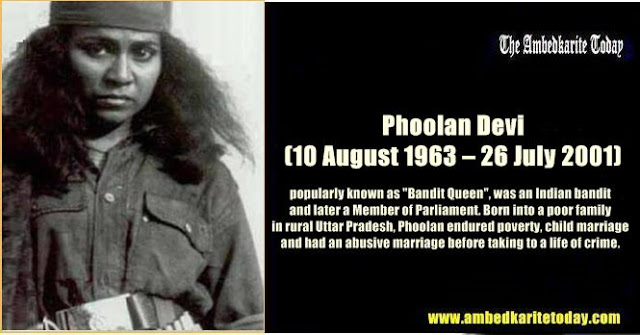

Know All About Phoolan Devi A Real Bandit Queen Of India

Phoolan Devi, Indian bandit and politician (born Aug. 10, 1963, Uttar Pradesh state, India—died July 25, 2001, New Delhi, India), was the notorious “Bandit Queen” who became legendary for both her acts of revenge on those who had abused her and her Robin Hood-like activities to aid the lower castes.

After being imprisoned, however, she became a member of the Lok Sabha, the lower house of Parliament, where she continued as a champion of the poor and oppressed. Devi’s life story was a mixture of fact and legend, beginning with her arranged marriage at age 11 to a man three times her age.

A year later, having been brutalized by him, she returned home, an act her family considered disgraceful. By the time she was in her early 20s, she had joined (or been kidnapped into) a gang of dacoits (bandits), been sexually assaulted numerous times—once by upper-caste landowners, Thakurs, in the village of Behmai—and left barren, and become the mistress of a dacoit leader. On Feb. 14, 1981, Devi led a notorious act of revenge known as the Saint Valentine’s Day massacre; some 20 of Behmai’s Thakurs were rounded up and shot in retribution for her gang rape.

This act intensified both her status in modern folklore and the police search for her. In 1983, in poor health and exhausted by the struggle to stay hidden, Devi negotiated her surrender to avoid a death sentence. Although she agreed to 8 years’ imprisonment, she ended up being jailed for 11 years, without trial, and gained release only through the efforts of the lower-caste chief minister of Uttar Pradesh. In 1994, shortly before her release, she was the subject of the Bollywood film Bandit Queen. In 1996, Devi took advantage of her cult status and, as a member of the Samajwadi Party, won election to Parliament. She lost her seat two years later but regained it in 1999. Devi was killed when masked assassins opened fire on her outside her home.

Early life Of Phoolan Devi

Phoolan was born into the Mallah (boatmen) caste, in the small village of Ghura Ka Purwa (also spelled Gorha ka Purwa) in Jalaun District, Uttar Pradesh. She was the fourth and youngest child of Moola and her husband Devi Din Mallah. Only she and one older sister survived to adulthood.

Phoolan’s family were very poor. The major asset owned by them was around one acre (0.4 hectare) of farmland with a large but very old Neem tree on it. When Phoolan was eleven years old, her paternal grandparents passed away in quick succession and her father’s elder brother became the head of the family. His son, Maya Din Mallah, proposed to cut down the Neem tree which occupied a largish patch of their one-acre farmland. He wanted to do this because the Neem tree was old and not very productive, and he wished to cultivate that patch of land with more profitable crops. Phoolan’s father acknowledged that there was some sense to this act, and agreed to it with mild protest.

However, the teenage Phoolan was incensed. She felt that since her father had no sons (only two daughters), her uncle and cousin were asserting sole claim on the family’s farmland inherited from the paternal grandfather. She confronted her much older cousin, taunted him publicly, called him a thief and repeatedly and, over a period of several weeks, showered abused and taunts upon him. One of the things attested about Phoolan by nearly every source is the fact that she had a very foul tongue, and routinely used abuses. Phoolan also attacked her cousin physically when he berated her for abusing him and making accusations against him. She then gathered a few village girls and staged a Dharna (sit-in) on the land, and did not budge even when the family elders tried to use force to drag them home. She was eventually beaten unconscious with a brick.

A few months after this incident, When Phoolan was eleven year old her family arranged for her to marry a man named Puttilal Mallah, who lived several hundred miles away and was three times her age. She suffered continuous beatings and sexual abuse at the hands of her husband and after several attempts at running away was returned to her family in ‘disgrace’.

In retaliation for the public and private humiliations heaped on him, and in order to teach her a lesson, Maya Din went to the local cops and accused Phoolan of stealing small items belonging to him, including a gold ring and a wrist-watch. The cops, who belonged to nearby villages, knew Phoolan and her family well, and they did what the family wanted. They kept Phoolan in jail for three days, physically abused her, and then let her off with a warning to behave better in future and live quietly without quarreling with her family or with others. Phoolan never forgave her cousin for this incident.

After Phoolan was released from jail, her parents once again wanted to send her to her husband. They approached Phoolan’s in-laws with the plea that she was now sixteen years of age and therefore old enough to begin cohabiting with her husband. They initially refused to take Phoolan back. However, they were themselves very poor, Phoolan’s husband was now twenty-eight years old, and it would be very difficult to find another bride for him, especially with one wife still living. Divorce was simply out of the question in that society. After Phoolan’s family offered generous gifts, they finally agreed to take her back. Phoolan’s parents performed the ceremony of gauna (after which a married woman begins to cohabit with her husband), took Phoolan to her husband’s house and left her there.

Within a few months, Phoolan, this time no longer a virgin, again returned to her parents. Shortly afterwards, her in-laws returned the gifts that Phoolan’s parents had given them and sent word that under no circumstances would they accept Phoolan back again. This was in 1979 and Phoolan was only a few months past her sixteenth birthday. She later claimed in her autobiography that her husband was a man of “very bad character.” A wife leaving her husband, or being abandoned by her husband, is a serious taboo in rural India, and Phoolan was marked as a social outcast.

Life as a Bandit or Dacoits

The region where Phoolan lived (Bundelkhand) is even today extremely poor, arid and devoid of industry; most of the able-bodied men migrate to large cities in search of manual work. During the period in question, industry was depressed even in the large cities, and daily life was a grim engagement with subsistence farming in a dry region with poor soil. It was not unusual for young men to seek escape from fruitless labour in the fields by running away to the nearby ravines (the main geographical feature of the region), forming groups of bandits, and plundering their more prosperous neighbours in the villages or passing townspeople on the highways.

|

| Credit – The Quint |

Shortly after her final sojourn in her husband’s house, and in the same year (1979), Phoolan fell in with one such gang of dacoits. How exactly this happened is unclear; some say that she was kidnapped by them because her “spirited temperament,” estrangement from her own family and outspoken rejection of her husband had attracted the attention of the bandits, while others say that she “walked away from her life.” In her autobiography, she merely says “kismet ko yehi manzoor tha” (“it was the dictate of fate”) that she become part of a gang of bandits.

Whether it was kidnapping or her own folly, Phoolan had immediate cause for regret. The gang leader, Babu Gujjar, raped and brutalized her for three days. At this juncture, Phoolan was saved from rape by Vikram Mallah, the second-in-command of the gang, who belonged to Phoolan’s own Mallah caste. In the altercation connected to the rape, Vikram Mallah killed Babu Gujjar. The next morning, he assumed leadership of the gang.

Relationship with Vikram Mallah

Undaunted by the fact that Vikram already had a wife and that she likewise had a husband, Phoolan and Vikram began cohabiting together. A few weeks later, the gang attacked the village where Phoolan’s husband lived. Phoolan herself dragged him out of his house and stabbed him in front of the villagers. The gang left him lying almost dead by the road, with a note warning older men not to marry young girls. The man survived, but carried a scar running down his abdomen for the rest of his life. Due to this incident, and because he legally remained Phoolan’s husband, the man was never able to marry again. He lived his life as a recluse because most people in the village began avoiding his company out of fear of the bandits.

Phoolan learned how to use a rifle from Vikram, and participated in the gang’s activities across Bundelkhand, which straddles the border between Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. These activities consisted of attacking and looting villages where upper-caste people lived, kidnapping relatively prosperous people for ransom, and committing occasional highway robberies which targeted flashy cars. Phoolan was the only woman member of that gang of dacoits. After every crime, she would visit a Durga temple and thank the Goddess for her protection. The gang’s main hideouts were in the ravines of the Chambal River.

Sometime later, Shri Ram and Lalla Ram, two upper-caste Rajput brothers who had been caught by the police, were released from jail and came back to the gang. They were outraged to hear of the murder of Babu Gujjar, their former leader, and held Phoolan responsible for inciting the act. They berated her for being a divisive wanton, and she answered them back with her characteristic foulness of tongue. Shri Ram then held her by the cuff of the neck and slapped her hard, and a scuffle ensued. Phoolan seized this opportunity to allege that Shri Ram had touched her breasts and molested her during the scuffle. As leader of the gang, Vikram Mallah berated Shri Ram for attacking a woman and made him apologise to Phoolan. Shri Ram and his brother smarted under this humiliation, which was exacerbated by the fact that Phoolan and Vikram both belonged to the Mallaah caste of boatmen, much lower than the land-owning Rajput caste to which they themselves belonged.

Whenever the gang ransacked a village, Shri Ram and Lalla Ram would make it a point to beat and insult the Mallahs of that village. This displeased the Mallah members of the bandit gang, many of whom left the gang. On the other hand, around a dozen Rajputs joined the gang at the invitation of Shri Ram and Lalla Ram, and the balance of power gradually shifted in favour of the Rajput caste. Vikram Mallah then suggested that the gang be divided into two, one comprising mainly Rajputs and the other mainly Mallahs. Shri Ram and Lalla Ram refused this suggestion on the grounds that the gang had always included a mixture of castes during the days of Babu Gujjar and his predecessors, and there was no reason to change. Meanwhile, the other Mallahs were also not happy with Vikram Mallah. The fact that he alone had a woman cohabiting with him incited jealousy; some of the other Mallahs had bonds of kinship with Vikram’s actual wife; and Phoolan’s tongue did not endear her to anyone who interacted with her. A few days after the proposal for division had been floated, a quarrel ensued between Shri Ram and Vikram Mallah. Apparently, Shri Ram made a disdaining comment about Phoolan’s morals, and Vikram responded with comments about Shri Ram’s womenfolk. A gunfight ensued. Vikram and Phoolan, with not a single supporter, managed to escape in the dark. However, they were later tracked down and Vikram Mallah was shot dead. Phoolan was taken by the victorious faction to the Rajput-dominated village of Behmai, home to Shri Ram, Lalla Ram and several of the new Rajput recruits.

According to legend, Vikram taught Phoolan, “If you are going to kill, kill twenty, not just one. For if you kill twenty, your fame will spread; if you kill only one, they will hang you as a murderess.”

Detainment in Behmai

Phoolan was locked up in a room in one of the houses in Behmai village. She was beaten, raped and humiliated by succession of several upper caste Thakur men over a period of three weeks. In a final indignity they paraded her naked around the village. She then managed to escape, after three weeks of captivity, with the help of a low-caste villager of Behmai and two Mallah members from Vikram’s gang, including Man Singh Mallah.

A new gang of Phoolan

Phoolan and Man Singh soon became lovers and joint leaders of a gang composed solely of Mallahs. The gang carried out a series of violent raids and robberies across Bundelkhand, usually (but not always) targeting upper-caste people. Some say that Phoolan targeted only the upper-caste people and shared the loot with the lower-caste people, but the Indian authorities claim this is a myth; there is no evidence of Phoolan or her partners in crime sharing money with anyone, whether low-caste or otherwise.

Massacre in Behmai

Several months after her escape from Behmai, Phoolan returned to the village to seek revenge. On the evening of 14 February 1981, at a time when a wedding was in progress in the village, Phoolan and her gang marched into Behmai dressed as police officers. Phoolan demanded that her tormentors “Sri Ram” and “Lala Ram” be produced.[citation needed] she allegedly said, The two men could not be found. And so Devi rounded up all the young men in the village and stood them in a line before a well. They were then marched in file to the river. At a green embankment they were ordered to kneel. There was a burst of gunfire and 22 men lay dead.

The Behmai massacre provoked outrage across the country. V. P. Singh, the then Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, resigned in the wake of the Behmai killings. A massive police manhunt was launched which however failed to locate Phoolan. It began to be said that the manhunt was not successful because Phoolan had the support of poor people in the region; stories on the Robin Hood model began circulating in the media. Phoolan began to be called the Bandit Queen, and she was glorified by sections of the Indian media as an intrepid and undaunted woman, the underdog struggling to survive in the world.

Surrender and jail term Of Phoolan Devi

Two years after the Behmai massacre, the police had still not captured Phoolan. The Indira Gandhi Government decided to negotiate a surrender. By this time, Phoolan was in poor health and most of her gang members were dead, some having died at the hands of the police, some others at the hands of rival gangs. In February 1983, she agreed to surrender to the authorities. However, she said that she didn’t trust the Uttar Pradesh Police and insisted that she would only surrender to the Madhya Pradesh Police. She also insisted that she would lay down her arms only before the pictures of Mahatma Gandhi and the Hindu goddess Durga, not to the police. She laid down four further conditions:

- A promise that the death penalty would not be imposed on any member of her gang who surrenders

- The term for the other members of the gang should not exceed eight years.

- A plot of land to be given to her

- Her entire family should be escorted by the police to witness her surrender ceremony

An unarmed police chief met her at a rendezvous in the Chambal ravines. They traveled to Bhind in Madhya Pradesh, where she laid down her rifle before the portraits of Gandhi and Goddess Durga. The onlookers included a crowd of around 10,000 people and 300 policemen, apart from the then chief minister of Madhya Pradesh, Arjun Singh. Other members of her gang also surrendered at the same time with her.

Phoolan was charged with as many as forty-eight crimes, including thirty charges of dacoity (banditry) and kidnapping. Her trial was delayed for eleven years, during which time she remained in prison as an undertrial. During this period, she was operated on for ovarian cysts and underwent a hysterectomy. The doctor of the hospital reportedly joked that “We don’t want Phoolan Devi breeding more Phoolan Devis“. She was finally released on parole in 1994 after intercession by Vishambhar Prasad Nishad, the leader of the Nishadha community (another name for the Mallah community of boatmen and fisherfolk). The Government of Uttar Pradesh, led by Mulayam Singh Yadav, withdrew all cases against her. This move sent shock-waves across India and became a matter of public discussion and controversy.

Phoolan Marriage with Ummed Singh

This time around Phoolan got married to Ummed Singh. Ummed Singh fought 2004 and 2009 election on Indian National Congress’s ticket. In 2014 he contested election on Bahujan Samaj Party’s ticket. Phoolan’s sister Munni Devi later accused him of being involved in Phoolan’s murder.

Member Of Parliament

In 1995, one year after her release, Phoolan was invited by Dr. Ramadoss (founder of Pattali Makkal Katchi) to participate in the conference about alcohol prohibition and women Pornography. This was her first conference after her release which began her Indian politics. However, Phoolan stood for election to the [11th Lok Sabha] from the Mirzapur constituency in [Uttar Pradesh]. She contested the election as a member of the Samajwadi Party of Mulayam Singh Yadav, whose government had withdrawn all cases against her and summarily released her from prison. She won the election and served as an MP during the term of the 11th Lok Sabha (1996–98). She lost her seat in the 1998 election but was re-elected in the 1999 election and was the sitting member of parliament for Mirzapur when she was assassinated.

| Loksabha Profile Of Phoolan Devi |

“As a Parliamentarian, she fought for women’s rights, an end to child marriage, and the rights of India’s poor. In a Che Guevara-type revision of history, though, Devi is remembered as a romantic Robin Hood figure, robbing the rich to help the poor, and not as a politician working to enact structural change in India’s social hierarchies.”

Death Of Bandit Queen Phoolan Davi

WHEN she was alive, Phoolan Devi had a larger-than-life image – of a victim of caste oppression and gender exploitation who fought back first by resorting to acts of gory revenge and later by moving on to the political plain. After her death, this image is sought to be metamorphosed into that of a phenomenal leader who waged a persistent struggle in the cause of the weak and the downtrodden, with a never-say-die spirit. The uncanny closeness of her sudden and gory death to the Uttar Pradesh Assembly elections and Chief Minister Rajnath Singh’s announcement of a system of “quota within quota“) for the most backward castes (MBCs) will ensure that her image is kept alive for long in the political arena of Uttar Pradesh. Her life and the manner of her death have the makings of a myth.

Phoolan Devi arrives at Parliament House on July 23, the first day of the monsoon session

Interestingly, as a member of the Lok Sabha Phoolan always jumped to the defence of her mentor Mulayam Singh Yadav whenever he was attacked by his rivals, mainly Bharatiya Janata Party members. She would try to shout them down. In death too, Phoolan seemed to have come to the rescue of the Samajwadi Party (S.P.) leader at a time when he was finding it difficult to counter Rajnath Singh’s MBC “brahmastra”. Phoolan belonged to the Malha community, one of the most backward castes among the Other Backward Classes (OBCs), which constitutes 7 per cent of the OBC population. Now Mulayam Singh can turn around and say that while Rajnath Singh talked about the welfare of the MBCs, in reality he was getting them killed. S.P. leaders have been making this allegation.

It is certain the S.P. will ensure that Phoolan’s killing in broad daylight in the high-security area in the national capital on July 25 will continue to haunt U.P. politics at least until the Assembly elections are over. The fact that the killing took place a few yards from Rajnath Singh’s residence on Ashoka Road and that his guards looked away when the shots were fired would only help the S.P.’s efforts. Thus, even before the details of her murder were known, the S.P. started attacking the BJP governments at the Centre and in Uttar Pradesh, accusing them of having withdrawn her security out of “caste bias“. There is, however, little evidence to show either that her security had been scaled down or that she had ever asked for more security.

Party general secretary Amar Singh blamed Home Minister L.K. Advani and Rajnath Singh for the murder. S.P. workers in New Delhi and Lucknow raised slogans like “Rajnath hatyara hai, ati pichhdon ko maara hai” (Rajnath is a killer, he has killed one from the most backward castes). Mulayam Singh Yadav forced Phoolan’s family members to conduct her cremation in Mirzapur, the Lok Sabha constituency in eastern Uttar Pradesh that she represented. Her body was taken by road from Varanasi to Mirzapur, although the plane that carried it to Varanasi could have landed in Mirzapur. The BJP draws its strength from eastern Uttar Pradesh, and Rajnath Singh and State BJP president Kalraj Mishra belong to this part of the State.

From the Chambal ravines, Phoolan had indeed come a long way, fighting every inch of it. The images of a diminutive woman in trousers, with a shawl thrown carelessly around her shoulders, a red bandana on her head, and an oversized gun in her hands at the time of her surrender to the Madhya Pradesh government in 1983 leave one wondering how she rose to become a people’s representative, fight for the rights of the oppressed, and create a niche for herself in the world of politics dominated by men. But she did it. She got elected to the Lok Sabha twice in the face of adversity. Her physical presence may not have created ripples in the caste politics of U.P. as the elections approach, but her death will certainly do that.

The S.P.’s attempt to draw political mileage from Phoolan’s death only serves to highlight the course U.P. politics has taken since the V.P. Singh government at the Centre decided to implement the Mandal Commission’s recommendations on reservations. Mulayam Singh Yadav’s decision to field Phoolan in Mirzapur in 1996 was primarily driven by considerations of caste arithmetic. The constituency has a significant population of Thakurs, besides Malhas and Julahas (weavers). His calculation was that if the Malhas and the Julahas got together, it was not difficult to beat the Thakurs. He was right. Phoolan, despite her background as a bandit, won the election with a convincing margin. After all, who could have symbolised the oppression unleashed by Thakurs in rural U.P. better than Phoolan, who was driven into the Chambal ravines by her traumatic experiences? She won despite the “vidhwa rath” (widow chariot) taken out by the widows of 20 Thakurs killed by her at Behmai in February 1981 and the propaganda by the BJP candidate who highlighted Phoolan’s lack of education, her violent past and the fact that she faced 48 criminal cases, including for 22 murder charges.

Phoolan lost the next round of parliamentary elections in 1998. But she bounced back to win in 1999, owing mainly to her rapport with her constituents and the hard work that she had put in as an MP. She came to be viewed as a saviour by many in her constituency, which was evident from the almost perpetual throng of supporters at her Ashoka Road residence. Her grieving supporters said after her death that nobody ever went back empty-handed from her house.

During the winter session of Parliament she was seen leading a group of supporters to Parliament House. She said: “They should see the proceedings. Then only would they understand how hard we fight for them. Then only would they understand the meaning of democracy.”

Sher Sing Rana Killed Phoolan Devi

The scanty details revealed by Pankaj alias Sher Singh Rana, the prime suspect in the case, indicated that the motive for the murder was personal rather than political. Pankaj, who was arrested at Dehra Dun on July 27, said that he killed Phoolan to avenge the 1981 massacre of Thakurs at Behmai. The Delhi Police, however, was looking at the possible involvement of her husband Ummed Singh, owing to property disputes and her threat to leave him out of her will. Besides, the police were also examining whether Phoolan’s turbulent marriage with Ummed and the involvement of Uma Kashyap, an associate of Phoolan, in the matter had something to do with the murder. On the day of the murder, Uma Kashyap was said to have reached Delhi in a car that Pankaj drove from Roorkee. She was reportedly in Phoolan’s house at the time of the murder.

The murder has put the Centre in the dock as far as the question of security of VIPs is concerned. VIP security has been a topic of discussion ever since the assassination of Indira Gandhi. The killers pumped bullets into Phoolan from a point-blank range, drove away in a car, abandoned it a little distance away, took an autorickshaw to the Inter State Bus Terminus, and allegedly boarded a bus to Dehra Dun. In short, they literally got away with murder in a high-security region. The spot of the crime is barely a kilometre from Parliament House and the Parliament Street Police Station.

References – Britannica, The Quint, Wikipedia, Frontline, feminisminindia