Earlier we suggested that the attachment of Untouchables to Congress during the 1930S and 40S was far less than is sometimes assumed. In the years after Independence Untouchable support for Congress clearly strengthened. From 1952 until 1989, with the exception of the post-Emergency election of 1977, Untouchables tended to function in both national and State elections as a ‘vote bank’ for Congress.

Their vote for Congress was a vote for the party of government, a party that had committed itself to a program of action on Untouchability and poverty. In rational terms and here their situation was similar to that of the Muslims there was little electoral choice open to Untouchables in most parts of the country. If the Left had developed more strength outside what became its strongholds in West Bengal and Kerala, the Untouchable attachment to Congress might have been less.

Thus in the very first post-Independence election of 1952 the Socialists won a good part of the Scheduled Caste vote. But this was the highpoint of their electoral experience in that State. It is only in the nineties that the logic of class (albeit often dressed in the garb of caste) is again being asserted across large parts of India, particularly the north.

While the Untouchables were a crucial Congress vote bank in India as a whole and in a majority of individual States, even before the recent flux they did not cling to Congress in regions where another party or move-ment rose to dominance. The major examples of long-term non-Congress dominance are West Bengal, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh.

Untouchables in the former two States have for a number of years had a strong identification with the Communist Party in its several divisions – in recent years predominantly with the dominant Communist Party of India (Marxist) (CPI(M)). A number of Ezhavas associated themselves with the fledgling Communist Party from the early 1940S, but with increasing prosperity the caste vote has been split along class lines between the Communists and Congress (Jeffrey 1974 59).

As to the other and poorer Untouchable castes of Kerala, these have been far less influen-tial in the councils of the Communist movement. But in conformity with the class divisions of Kerala politics, the Scheduled Castes have tended to gravitate towards the parties of the Left. In West Bengal, the Communist movement was slower to gain control of the State: the first United Front Government came to power in 1967, a decade after the first such govern-ment in Kerala.

Support for the CPI(M) in West Bengal has been broadly based and not confined to particular castes, but again the party has done particularly well among poorer voters and therefore among the Scheduled Castes. In short, the Untouchables of Kerala and West Bengal have behaved according to the logic of their class position within a polit-ical culture more directed to considerations of class than anywhere else in India. But from another perspective the Untouchables of these two States have been doing little different from their counterparts elsewhere in India. They have simply aligned themselves with the majority party – it is doubtful that most of these Untouchables have been affected with any special passion for Marxism.

In Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh regional parties have come to dominate State politics. The non-Brahmin movement of Tamil Nadu spawned a succession of parties – first the Justice Party and after Independence the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and Anna DMK. Anti-Brahminism has been joined with Dravidian nationalism to produce a highly distinctive political and popular culture. For decades State elections have largely been fought out between the DMK and Anna DMK, each of which lays claim to the common culture.

The Untouchables were relatively slow to embrace the culture, given their break with the non-Brahmin movement in the early 1920S and their subsequent attraction to Congress. But with the dominance asserted by the DMK and then the Anna DMK from the late 196os, the Untouchables have been rolled up into the prevailing politics of the State. But since Congress has often been able to engineer electoral accommodations with one or other of the three dominant leaders over the last three decades -Karunanidhi and the film star politicians M. Ramachandran (MGR) and Jayalalitha – many Tamil Untouchables have voted for the DMK or Anna DMK at State elections and for Congress in national elections.

If we turn to Andhra, the emergence of a dominant regional party is more recent. The Telegu Desam party of Andhra has been built around N. I Rama Rao, the charismatic Telegu movie star. NTR’s style, like that of the Tamil leaders, was best described as populist, and his party attracted Untouch-able voters as it moved into a position of dominance. But Telegu Desam has not been so dominant even in State elections as have successive regional parties in Tamil Nadu. In short, and unlike the position in the Communist States, in both Tamil Nadu and Andhra the Untouchables have not been wholly lost to Congress.

Within Congress the importance of the Untouchable vote did not translate itself into great influence for individual Untouchables in either the organisation or the ministry. In particular, the building of the com-pensatory discrimination system arose more from the arithmetic of elec-tions and the goodwill of sections of the elite than from the efforts of Dalit parliamentarians. Jagjivan Ram was alone as a Scheduled Caste politician in becoming a genuinely national figure through Congress.

There have been a couple of Chief Ministers – one of them was Bhole Paswan Shastri, who three times held this position in Bihar for very brief periods in the 1950s. Bhole Paswan was respected for his modesty, dignity and probity, but he made no deep mark on even State politics: his life and career are discussed in the next chapter. A small number of other State and national politicians have gained a measure of ministerial seniority, but none has had either a long period at the apex of ministerial service or any sub-stantial political base. Just why this is the case may require an answer at several levels.

Perhaps it is to be expected that a collection of castes dis-tinguished by their overall subordination would not produce the highest crop of educated, experienced and generally talented politicians. Over time the gap in education and sophistication between Untouchables and, say, Brahmins has diminished, and the depth of talent among Untouchable aspirants for high office is no doubt growing. But it will not help the Untouchable cause to deny that there has been a gap at all. On the other hand, issues of talent and preparation for public office can scarcely constitute the primary explanation for the low representation of Untouchables at the highest political levels.

There are persistent suggestions that Dalit politicians have not thrived within Congress if they have too strenuously promoted the cause of their own people. This is an explanation sometimes offered in relation to Yogendra Makwana, a talented and energetic Minister of the early 19805 whose career did not prosper under either Indira or Rajiv Gandhi.

Makwana can be contrasted with Buta Singh, a Mazhabi Sikh (converted from a Sweeper caste) who rose to the position of Home Minister under the same Prime Ministers. Buta Singh (later relegated to a junior portfo-lio under Narasimha Rao) was known for his political savoir-faire and his loyalty to the Nehru family, rather than for any particular zeal for the problems of the Scheduled Castes. Of course, as a category Prime Ministers tend to distrust colleagues of whatever community if they have a political base or agenda independent of their own.

Yet it remains an important truth that the ideological and social makeup of Congress has made it less than welcoming to highly assertive advocates of the Untouchable cause. Low social standing has also made individual Untouchable spokesmen relatively easy targets for political demolition. Untouchables have therefore tended to construct their political careers as dependants within factions led by high-caste politicians. It is impossible to think of a single example of a substantial multi-caste faction leader who is/was himself a Dalit.

Something more needs to be said here about the career of Jagjivan Ram. Under the patronage of the Nehrus Jagjivan Ram rose to the posi-tion of Defence Minister. He climbed a rung higher to the post of Deputy Prime Minister under Charan Singh in 1979, a position that rewarded him for ostensibly having delivered the Untouchable vote to the Janata coalition in the extraordinary election of 1977. Jagjivan Ram’s career is notable for its extraordinary longevity, a consequence of both his compe-tence and also his carefulness not to engage in dissent and controversy. On both counts he was the ideal Untouchable for Congress to promote through its ranks.

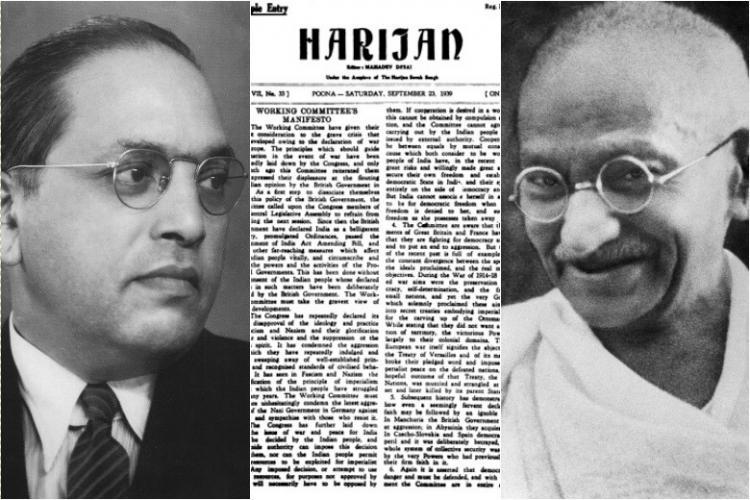

Jagjivan Ram was the only significant Untouchable to have played a strong part in Gandhi’s Harijan movement of the 1930s. He became President of the All-India Depressed Classes League formed in 1935, and was elected to the Bihar Assembly for Congress in the election of 1937. In 1946 he was appointed Labour Minister in the Viceroy’s Executive Council, and from then (with a short interregnum during the Kamaraj Plan) he held Cabinet positions in successive Congress Governments and later the Janata Government until its electoral defeat in 1980.

Once he became a Minister he seems not to have made Untouchability a central preoccupation in either speech or action. His most extensive public comment is to be found in a small book published in 1980, Caste Challenge in India. This book is neither novel in its analysis nor specially hard-hitting, though clearly its author believed that he could be more expansive now that his career had come to an end. Thus despite the book’s mild tone, the preface contains the propitiatory remark that his views are offered ‘not to hurt any class or caste but to provide a brief historical account of the Hindu social system… and the miserable condition of the Scheduled Castes and Tribes’ (Ram 1980: 5-6).

It is difficult to estimate the power that Jagjivan Ram wielded within Congress. He played an important role at several critical moments in the post-Nehru era: he supported Indira Gandhi’s candidacy for Prime Minister in 1966, stayed with her when Congress split in 1969, and quit the party in 1977. Paul Brass observes that he was ‘always thought to be able to control 40 to 6o votes in Parliament and was deferred to in the Congress for that reason’ (Brass 1990: 208-9).

But the quality of this ‘control’ is not self-evident. It seems likely that he had more power than anyone else in selecting Scheduled Caste candidates for Congress from the reserved seats in Bihar, and he may have exercised some power in neighbouring Uttar Pradesh and perhaps other States too; his qualifica-tion was not only his long career but also the fact that his own Chamar caste was by far the largest Scheduled Caste of north India. Presumably Ram’s role in the selection of candidates invested him with some influ-ence in relation to the MPs who depended upon his continued support.

Thus it is possible that he was able to deliver votes to Indira Gandhi in the succession contest after the death of Prime Minister Shastri and in the Congress split of 1969. But when he left Congress in 1977 he failed to persuade any of the Party’s other Scheduled Caste MPs to accompany him. And more importantly, there is no evidence that he either sought or was able to mobilise a bloc of MPs in order to make policy gains for the Scheduled Castes within Cabinet.

Any part he may have played in either the development or maintenance of programs and policies favourable to Untouchables was for the most part hidden. It is suggested that when he was Minister for Railways he was successful in rapidly building up the Scheduled Caste (allegedly mainly Chamar) component of the railways workforce. And in his other portfolios too he may have exerted pressure for the legal quotas to be filled.

But by far his most potent moment came when he left Congress on the eve of the post-Emergency election in 1977, since his departure seemed to crystallise the first large anti-Congress vote among north Indian Untouchables. This vote was of major signifi-cance to the outcome of the election. But the limits of Jagjivan Ram’s electoral appeal and the special nature of the 1977 election were revealed when he failed to prevent the return of these same voters to Congress in 1980.

There is no single set of characteristics common to the leadership of Congress over the last half century, but a glance at the background of those at the very apex of Indian politics is instructive. All five Congress Prime Ministers have been Brahmins, including three from the Nehru family. In the non-Congress Governments of 1977-9 and 1989-91 two of the Prime Ministers were Rajputs, one was a Brahmin and the third was Charan Singh, a Jat, and till then the only Prime Minister from a background other than that of a twice-born (upper) caste.

Now Deve Gowda, short-lived Prime Minister after the 1996 election, shares that status with Charan Singh. While it is not possible to extrapolate from the caste background of Prime Ministers to the background of Congress leaders in general, high-caste and particularly Brahmin domination of the most senior positions has been characteristic of Congress throughout its long history. Nor is this phenomenon confined to Congress. Atul Kohli has produced figures to show that both Congress and Communist Party dominated Governments in West Bengal have had a strikingly skewed caste composition.

The caste of Ministers in Congress Governments in West Bengal between 1952 and 1962 was 23 per cent Brahmin, 31 per cent Kayastha, 24 per cent Vaishya, and only 2 per cent Scheduled Caste. In the case of Governments led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist) between 1977 and 1982 there were even more Brahmins than in the Congress Governments, over 35 per cent; the number of Kayasthas (:3′ per cent) and Vaishyas (23 per cent) was almost the same as in Congress Governments, while Scheduled Caste representation was marginally lower at 1.5 per cent (Kohli 1990: 374). These figures must be read in the context of a State which has the highest concentration of Scheduled Caste people in the country – now almost 24 per cent (Census 1991).

Demonstrably, the many Scheduled Caste members of the West Bengal Assembly have almost no chance of rising to the position of Minister. Their representation is even lower if inferior Ministers – Ministers of State and Deputy Ministers – are left out. In the Governments formed after the elections of 1952, 1957, 1962, 1977 and 1982 there was not a single Scheduled Caste member of the Council of Ministers, Of course, it is not merely the Scheduled Castes that have been grossly underrepresented in West Bengali Cabinets – the same is true for Scheduled Tribes, Muslims and lower-caste Hindus.

A similar, if less pronounced, pattern is true of the organisational wing of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), and given the ideological orientation of the party it is worth attending to this phenomenon more closely.4 In both Kerala and West Bengal Untouchables are scarcely represented at the highest levels of the Party. In Kerala, those who have risen to leading Party positions from poor backgrounds have almost always come from ‘proletarian’ unions of the towns. The Ezhava domi-nated bidi workers union is one such example.

Scheduled Caste workers in Kerala still tend to be agricultural labourers, and they have found it impossible to rise to the top of the Party hierarchy. In West Bengal, until the late sixties the Party was essentially an urban and high-caste organisa-tion. With the later focus on agrarian problems there has been a growing membership drawn from the villages. Scheduled Caste membership is now in double figures, most of it rural in origin (though not usually drawn from the ranks of agricultural labourers, the lowest agrarian category). But even if such people are as likely as anyone else to rise to the top of the Party – a questionable assumption – it would take considerable time before their presence might be felt.

It is not open to infer the whole character of a government or a political party from the caste composition of its senior members. The Communist governments of West Bengal and Kerala have been among the best State governments in India in terms of both probity and service to their poorer citizens. But even these governments are vulnerable to criticism for their insufficient attention to those at the very bottom of the social hierarchy. For example, both governments have frequently been attacked for their failure to meet job reservation quotas.

Presumably this failure can be said to arise from an ideological antipathy to programs constructed on the basis of social primordialism (caste). But it can also scarcely be irrelevant that reservation is adverse to the interests of large proportions of the castes that predominate within the government.5 Even in less intensely caste conscious West Bengal it cannot be assumed that Communist Ministers are effectively without caste (or class). This is not to propose the existence of a caste conspiracy or even a lack of goodwill towards the underprivileged. It is merely to recognise that it is difficult to induce and sustain a sense of urgency about the claims of out-groups in the absence of their own advocates.

A deeper criticism of the Communist governments can be levelled at their agrarian programs. Thus Kerala has one of the poorer records of land reform among the various States. There has been only a slight amount of redistribution of agricultural land, and agricultural labourers (many of them Untouchables) have had to be content with gaining own-ership of the land on which their ‘hutment’ is built within the village. Kerala has done far better in the matter of fixing minimum wages for its agricultural labourers, though here there have been some unfortunate consequences.

Partly because of the resulting high cost of labour there has been a radical reduction in the amount of work available to Kerala labourers: mechanisation, leaving land fallow, and employment of out-of-State workers have been options preferred by many employers. The West Bengal experience on the same two issues has been the reverse of that of Kerala. West Bengal has done much better in the area of land redistribu-tion, and it has also accomplished significant reforms for sharecroppers. But the CPI(M) Government has paid little attention to the interests of the army of agricultural labourers in the State.

A large proportion of these labourers are, of course, from the Scheduled Castes, and their rates of pay and general living conditions are at the poorer end of the national scale. Nor is Operation Barga (see above, p. 155) beyond criticism. These reforms were abandoned at the highly incomplete point when further action would have directly injured the interests of small, usually absentee, landlords. Many of these mainly high-caste people have been supporters of the CPI(M) regime, and the decision can therefore be painted in tones of political pragmatism. Moreover, in an ‘encircled’ polity such as West Bengal there are undoubtedly limits to just how much redistribution is a possibility. Clearly we must be careful not to repackage the whole huge problem of Indian poverty and inequality into the receptacle of caste -this will make no analytical sense, nor indicate a way out of the practical condition. Nonetheless, we doubt it can be said that ties of caste and com-munity, wrapped up in positions of class, are of no relevance to the policy and performance of the Government of West Bengal.

The above question can be crystallised by reference to Ambedkar’s description of Indian Communists as ‘a bunch of Brahman boys’ (Harrison 1960: 191). He was referring not only to the number of Brahmins within the Party, but also to discriminatory attitudes and blind-ness to the problems of the Untouchables. If we discount the hyperbole, the observation contains a (slippery) grain of truth. On the one hand we should not subscribe to the false proposition that only the representatives of a particular community are capable of working for the good of that community. But we must also recognise that a community or a people needs to speak for itself if its interests and potential are to be realised to any great degree.

This is the dialectic embedded in the issue of Untouchable representation in contemporary politics. Thus it is reason-able to assume that greater Untouchable representation at the highest levels would produce outcomes more favourable to their own people than occurs through government dominated by the high castes. The benefits would no doubt range from individual allocations (such as jobs, licences, contracts) to broader policy. To give one small but important example of possible policy, greater Untouchable presence in government could conceivably lead to the application of more pressure towards the exten-sion of affirmative action into private- and not merely public-sector enter-prises. This is exactly the sort of non-revolutionary but quite far-reaching change that is potentially within the realm of government action in India.

EDITORS NOTE – THIS ARTICLE FROM THE BOOK THE UNTOUCHABLES SUBORDINATION, POVERTY AND THE STATE IN MODERN INDIA BY OLIVER MENDELSOHN & MARIKA VICZIANY