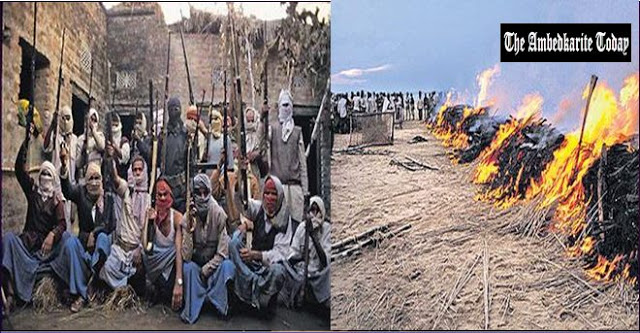

On a chilly December night 22 years ago, 58 villagers of Laxmanpur-Bathe in south Bihar’s Arwal district were murdered in cold blood. All the victims of the massacre were Dalits and many among them children, the youngest being a one-year-old, and pregnant women.

On the evening of December 1, 1997, armed sena activists crossed the Sone river into the village of Laxmanpur-Bathe where 180 families lived. They raided fourteen Dalit homes and killed a total of sixty-one people: sixteen children, twenty-seven women, and eighteen men. In some families, three generations were killed. Twenty people were also seriously injured.

As most of the men fled the village when the attack began, women and children numbered high among the fatalities. During the attack, at least five girls around fifteen years of age were raped and mutilated before being shot in the chest by members of the Ranvir Sena. Most of the victims allegedly belonged to families of Party Unity supporters; the group had been demanding more equitable land distribution in the area.

The village of Laxmanpur-Bathe has no electricity and is virtually inaccessible by road. In crossing the Sone river to reach the village, sena members reportedly also killed five members of the Mallah (fisherman) community and murdered the three Mallah boatmen who had ferried them across the river on their way back. According to newspaper reports, the main reason for the attack was that the Bhumihars wanted to seize fifty acres of land that had been earmarked for distribution among the landless laborers of the village.

A group of peasants, reportedly affiliated with Naxalite activity, was ready to take up arms against them. Authorities apparently knew of the tensions but “had not cared to intervene in the land dispute and nip the trouble in the bud and instead allowed things to come to a head.” Following widespread publicity about the massacre, Bihar Chief Minister Rabri Devi suspended the Jehanabad district superintendent of police and replaced several senior officers.

Human Rights Watch visited the village on February 25, 1998. According to villagers who survived the attack, close to one hundred members of the Ranvir Sena arrived en masse and entered the front houses of the village: “Their strategy was to do everything simultaneously so that no one could be forewarned.” Human Rights Watch visited a house in which seven family members were killed. Only the father and one son survived. Vinod Paswan, the son, described the attack:

Fifteen men surrounded the house, and five came in. My sister hid me behind the grain storage. They broke the door down. My sisters, brothers, and mother were killed… The men didn’t say anything. They just started shooting. They yelled, “Long live Ranvir Sena,” as they were leaving.

At the time of the attack, the father, Ramchela Paswan, was away in the fields. When he returned, he found seven of his family members shot in his house: “I started beating my chest and screaming that no one is left. No one has been saved from my family. Then my son came out saying he that he had not been killed.”

Human Rights Watch also interviewed seven female residents of the village, many of whom witnessed the rape, mutilation and murder of five girls. Thirty-two-year-old Surajmani Devi recounted what she saw:

Everyone was shot in the chest. I also saw that the panties were torn. One girl was Prabha. She was fifteen years old. She was supposed to go to her husband’s house two to three days later. They also cut her breast and shot her in the chest. Another was Manmatiya, also fifteen. They raped her and cut off her breast. The girls were all naked, and their panties were ripped. They also shot them in the vagina. There were five girls in all. All five were raped. All were fifteen or younger. All their breasts were cut off.

Twenty-five-year-old Mahurti Devi was shot in the stomach but survived her injuries after extensive surgery. She had returned home after a dispute with her husband and was living in her mother’s house. She recalled:

They broke in and tried to open our box of valuables. They couldn’t so they took my chain and earrings off my body. There were ten to twelve of them in the house. They didn’t wear any masks. I said I had nothing. They said open everything. My mother was shot, and she fell down. They flashed a torch on my face. Then they shot me, and I fell down.The police took me to the hospital. After a three-day operation I came to, and the police took a report from me. Some people have been arrested, others are still free. They looted all the houses.

At the time of the massacre, Jasudevi was at her husband’s home in another village. She arrived in Bathe the morning after the attack to find her two sisters-in-law and her fifteen-year-old niece shot to death. “My niece was supposed to go to her husband’s house the same day. She was expecting a child. When I found her it looked like she was trying to run away when she was shot.” Seven-year-old Mahesh Kumar was being held by his mother when she was shot. She fell forward and protected his body with her own. She then died.

Local police had been aware of the possibility of violence long before the Bathe massacre. On November 25, 1997, sena leaders openly held a strategy meeting seven kilometers away from Bathe. Sena leader Shamsher Bahadur Singh had also been touring the area in the months before the massacre openly seeking donations from supporters. Police officers claimed to be aware of these meetings but dismissed them as routine—missing yet another opportunity to intervene and preempt a sena attack. One officer was quoted as saying, “It’s like crying wolf. The Communist Party of India (M-L) keeps sending us complaint letters every week, we can’t take action every time.”

According to members of Bihar Dalit Vikas Samiti, a grassroots organization, the events that unfolded in Bathe were more complex than a random attack on a Dalit hamlet:

CPI was organizing in Bathe because the residents were so poor and exploited, they couldn’t even feed themselves after a full day’s work. When they asked for more wages, they were beaten down even more. Some CPI(M-L) and Party Unity people had a split. A few people leftthem and gave information about party activities to landlords. The landlords contacted Ranvir Sena in Bhojpur, saying that they needed help controlling them. The Ranvir Sena came out at 4:00 p.m. They ate and drank liquor with the landlords and attacked at 9:00 p.m. They had a list of whom to attack but got drunk and killed anyone and everyone.

The activists also claimed that the purpose of Bathe was “to teach others not to rebel or raise a voice. In so doing women became vulnerable and were sexually assaulted… They raped women and cut off their breasts. A woman whose pregnancy was nearly complete was shot in the stomach. They said that otherwise the child will grow up to be a rebel.”

Life for most in the village has been disrupted. At the time of the Human Rights Watch visit, children were unable to go to school because a makeshift police camp had been located on school grounds. None of the adults were working. Villagers complained, “There is no work, all has stopped. Since they [Bhumihars] are the landed families, our people don’t get to work in their fields.”

Since the massacre, police protection in Bathe has remained grossly inadequate. The Bihar government announced soon after the Bathe killings that police would be deployed in the area to set up camp and maintain law and order. However, when parliamentary elections were later announced, the police force was directed to control election-related violence. Despite their dual assignment of controlling the Ranvir Sena and watching the polls, the police seemed more intent on conducting raids on Dalit villages in the name of controlling “extremism” and seeking out Naxalite cadres than on protecting Dalit villagers. According to a member of BDVS, “Bathe protection is near the poor but it only benefits the rich. Police always go to the landlords’ houses… All their needs are taken care of byupper castes. If someone calls a meeting they won’t come. They say we don’t have time. They just do flag marches.”

At the time Human Rights Watch visited the village, the Dalit residents of Bathe feared another attack:

Fifteen to twenty days ago we received a message that they will sprinkle petrol on the houses of villages and set them on fire—the houses of those that didn’t get killed the first time around. We told the police. They said we are here so nothing will happen, but the police are protecting them. They are stationed in the Ranvir Sena tola [hamlet]. Police are helping the Ranvir Sena. The accused are moving around freely. So we feel that the culprits are being protected.

Human Rights Watch also spoke to police officers stationed in the village school. Officer In-Charge Amay Kumar Singh informed us that a total of twenty-six police officers were present in the village. He claimed that the police arrived soon after the massacre. According to Singh, twenty-five of the twenty-six perpetrators identified by villagers had been arrested but at the time of the interview (two months after the events) had not been formally charged. He claimed that the police were providing security for all villagers and that new threats had not been reported to them.

Like many officers, Singh claimed that police response to attacks is hindered by insufficient funding, infrastructure, and equipment for village-based police camps. These arguments fail, however, when one notes the frequency of police search and raid operations on remote Dalit villages. Though Singh believed that his officers had enough guns to provide security, and were able to communicate quickly with the area police station, he claimed that more men and more facilities were needed and that the roads to the village were in very poor condition. Road construction had begun soon after the massacre but came to a halt when “VIPs” stopped visiting the area. “We have no car. Look at our conditions. We are sleeping on the ground,” Singh complained. Deputy General of Police Saxenaalso reported that the local police station was poorly equipped and there was not enough personnel. “That’s why we couldn’t prevent this,” he said.

On January 9, 1998, nine people suspected to be supporters of the Ranvir Sena were killed by CPI(M-L) activists in Chouram village, forty-five kilometers from Jehanabad. The killings were reportedly in retaliation for the Bathe massacre. The attackers opened fire indiscriminately on the victims as they were returning home from a funeral.160 Several Dalits in the Bathe area were subsequently taken into custody by the police. Bathe villagers claim that the sena members were actually killed by Marxist-Leninist party members who were not from their village: “Police have been harassing Dalits for fifteen kilometers around this village. No one cares about the sixty-one people who died here. Everyone cares about those nine. The Ranvir Sena says that they will take ninety for those nine killed.”

Despite the arrests immediately after the massacre, as of February 1999 none of the sena members responsible for the Bathe attack had been prosecuted.

Reference- Human Rights Watch