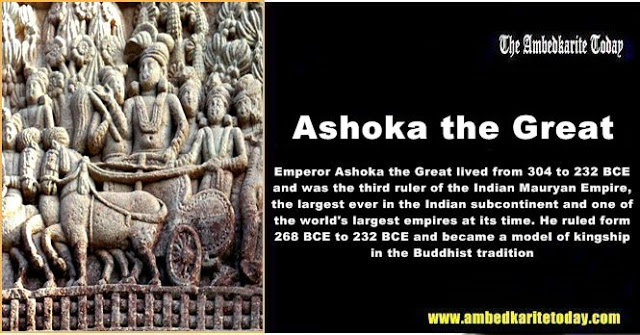

Ashoka The Great

Emperor Ashoka the Great (sometimes spelt Aśoka) lived from 304 to 232 BCE and was the third ruler of the Indian Mauryan Empire, the largest ever in the Indian subcontinent and one of the world’s largest empires at its time. He ruled form 268 BCE to 232 BCE and became a model of kingship in the Buddhist tradition. Under Ashoka India had an estimated population of 30 million, much higher than any of the contemporary Hellenistic kingdoms. After Ashoka’s death, however, the Mauryan dynasty came to an end and its empire dissolved.

Ashoka’s Rule

In the beginning, Ashoka ruled the empire like his grandfather did, in an efficient but cruel way. He used military strength in order to expand the empire and created sadistic rules against criminals. A Chinese traveller named Xuanzang (Hsüan-tsang) who visited India for several years during the 7th century CE, reports that even during his time, about 900 years after the time of Ashoka, Hindu tradition still remembered the prison Ashoka had established in the north of the capital as “Ashoka’s hell”. Ashoka ordered that prisoners should be subject to all imagined and unimagined tortures and nobody should ever leave the prison alive.

During the expansion of the Mauryan Empire, Ashoka led a war against a feudal state named Kalinga (present day Orissa) with the goal of annexing its territory, something that his grandfather had already attempted to do. The conflict took place around 261 BCE and it is considered one of the most brutal and bloodiest wars in world history. The people from Kalinga defended themselves stubbornly, keeping their honour but losing the war: Ashoka’s military strength was far beyond Kalinga’s. The disaster in Kalinga was supreme: with around 300,000 casualties, the city devastated and thousands of surviving men, women and children deported.

AFTER THE WAR OF KALINGA, ASHOKA CONTROLLED ALL THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT EXCEPT FOR THE EXTREME SOUTHERN PART.

What happened after this war has been subject to numerous stories and it is not easy to make a sharp distinction between facts and fiction. What is actually supported by historical evidence is that Ashoka issued an edict expressing his regret for the suffering inflicted in Kalinga and assuring that he would renounce war and embrace the propagation of dharma. What Ashoka meant by dharma is not entirely clear: some believe that he was referring to the teachings of the Buddha and, therefore, he was expressing his conversion to Buddhism. But the word dharma, in the context of Ashoka, had also other meanings not necessarily linked to Buddhism. It is true, however, that in subsequent inscriptions Ashoka specifically mentions Buddhist sites and Buddhist texts, but what he meant by the word dharma seems to be more related to morals, social concerns and religious tolerance rather than Buddhism.

The Edicts of Ashoka

After the war of Kalinga, Ashoka controlled all the Indian subcontinent except for the extreme southern part and he could have easily controlled that remaining part as well, but he decided not to. Some versions say that Ashoka was sickened by the slaughter of the war and refused to keep on fighting. Whatever his reasons were, Ashoka stopped his expansion policy and India turned into a prosperous and peaceful place for the years to come.

|

| Greek and Aramaic inscriptions by king Ashoka |

Ashoka began to issue one of the most famous edicts in the history of government and instructed his officials to carve them on rocks and pillars, in line with the local dialects and in a very simple fashion. In the rock edicts, Ashoka talks about religious freedom and religious tolerance, he instructs his officials to help the poor and the elderly, establishes medical facilities for humans and animals, commands obedience to parents, respect for elders, generosity for all priests and ascetic orders no matter their creed, orders fruit and shade trees to be planted and also wells to be dug along the roads so travellers can benefit from them.

However attractive all this edicts might seem, the reality is that some sectors of Indian society were truly upset about them. Brahman priests saw in them a serious limitation to their ancient ceremonies involving animal sacrifices, since the taking of animal life was no longer an easy business and hunters along with fishermen were equally angry about this. Peasants were also affected by this and were upset when officials told them that “chaff must not be set on fire along with the living things in it”. Brutal or peaceful, it seems that no ruler can fully satisfy the people.

Kalinga war and conversion to Buddhism

Kanaganahalli inscribed panel portraying Asoka with Brahmi label “King Asoka”, 1st-3rd century CE. Ashoka’s own inscriptions mention that he conquered the Kalinga region during his 8th regnal year: the destruction caused during the war made him repent violence, and in the subsequent years, he was drawn towards Buddhism. Edict 13 of the Edicts of Ashoka Rock Inscriptions expresses the great remorse the king felt after observing the destruction of Kalinga:

Directly after the Kalingas had been annexed began His Sacred Majesty’s zealous protection of the Law of Piety, his love of that Law, and his inculcation of that Law. Thence arises the remorse of His Sacred Majesty for having conquered the Kalingas, because the conquest of a country previously unconquered involves the slaughter, death, and carrying away captive of the people. That is a matter of profound sorrow and regret to His Sacred Majesty.

On the other hand, the Sri Lankan tradition suggests that Ashoka was already a devoted Buddhist by his 8th regnal year, having converted to Buddhism during his 4th regnal year, and having constructed 84,000 viharas during his 5th–7th regnal years. The Buddhist legends make no mention of Kalinga campaign.

Based on Sri Lankan tradition, some scholars – such as Eggermont – believe that Ashoka converted to Buddhism before the Kalinga war. Critics of this theory argue that if Ashoka was already a Buddhist, he would not have waged the violent Kalinga War. Eggermont explains this anamoly by theorising that Ashoka had his own interpretation of the “Middle Way“.

Some earlier writers believed that Ashoka dramatically converted to Buddhism after seeing the suffering caused by the war, since his Major Rock Edict 13 states that he became closer to the dhamma after the annexation of Kalinga. However, even if Ashoka converted to Buddhism after the war, epigraphic evidence suggests that his conversion was a gradual process rather than a dramatic event. For example, in a Minor Rock Edict issued during his 13th regnal year (five years after the Kalinga campaign), he states that he had been an upasaka (lay Buddhist) for more than two and a half years, but did not make much progress; in the past year, he was drawn closer to the sangha, and became a more ardent follower.

The war

According to Ashoka’s Major Rock Edict 13, he conquered Kalinga 8 years after his ascension to the throne. The edict states that during his conquest of Kalinga, 100,000 men and animals were killed in action; many times that number “perished”; and 150,000 men and animals were carried away from Kalinga as captives. Ashoka states that the repentance of these sufferings caused him to devote himself to the practice and propagation of dharma. He proclaims that he now considered the slaughter, death and deportation caused during the conquest of a country painful and deplorable; and that he considered the suffering caused to the religious people and householders even more deplorable.

This edict has been found inscribed at several places, including Erragudi, Girnar, Kalsi, Maneshra, Shahbazgarhi and Kandahar. However, is omitted in Ashoka’s inscriptions found in the Kalinga region, where the Rock Edicts 13 and 14 have been replaced by two separate edicts that make no mention of Ashoka’s remorse. It is possible that Ashoka did not consider it politically appropriate to make such a confession to the people of Kalinga. Another possibility is the Kalinga war and its consequences, as described in Ashoka’s rock edicts, are “more imaginary than real”: this description is meant to impress those far removed from the scene, and thus, unable to verify its accuracy.

Ancient sources do not mention any other military activity of Ashoka, although the 16th century writer Taranatha claims that Ashoka conquered the entire Jambudvipa.

First contact with Buddhism

Different sources give different accounts of Ashoka’s conversion to Buddhism.

According to Sri Lankan tradition, Ashoka’s father Bindusara was a devotee of Brahmanism, and his mother Dharma was a devotee of Ajivikas. The Samantapasadika states that Ashoka followed non-Buddhist sects during the first three years of his reign. The Sri Lankan texts add that Ashoka was not happy with the behaviour of the Brahmins who received his alms daily. His courtiers produced some Ajivika and Nigantha teachers before him, but these also failed to impress him.

The Dipavamsa states that Ashoka invited several non-Buddhist religious leaders to his palace, and bestowed great gifts upon them in hope that they would be able to answer a question posed by the king. The text does not state what the question was, but mentions that none of the invitees were able to answer it. One day, Ashoka saw a young Buddhist monk called Nigrodha (or Nyagrodha), who was looking for alms on a road in Pataliputra. He was the king’s nephew, although the king was not aware of this: he was a posthumous son of Ashoka’s eldest brother Sumana, whom Ashoka had killed during the conflict for the throne. Ashoka was impressed by Nigrodha’s tranquil and fearless appearance, and asked him to teach him his faith. In response, Nigrodha offered him a sermon on appamada (earnestness). Impressed by the sermon, Ashoka offered Nigrodha 400,000 silver coins and 8 daily portions of rice. The king became a Buddhist upasaka, and started visiting the Kukkutarama shrine at Pataliputra. At the temple, he met the Buddhist monk Moggaliputta Tissa, and became more devoted to the Buddhist faith.The veracity of this story is not certain. This legend about Ashoka’s search for a worthy teacher may be aimed at explaining why Ashoka did not adopt Jainism, another major contemporary faith that advocates non-violence and compassion. The legend suggests that Ashoka was not attracted to Buddhism because he was looking for such a faith, rather, for a competent spiritual teacher. The Sri Lankan tradition adds that during his 6th regnal year, Ashoka’s son Mahinda became a Buddhist monk, and his daughter became a Buddhist nun.

A story in Divyavadana attributes Ashoka’s conversion to the Buddhist monk Samudra, who was an ex-merchant from Shravasti. According to this account, Samudra was imprisoned in Ashoka’s “Hell”, but saved himself using his miraculous powers. When Ashoka heard about this, he visited the monk, and was further impressed by a series of miracles performed by the monk. He then became a Buddhist. A story in the Ashokavadana states that Samudra was a merchant’s son, and was a 12-year-old boy when he met Ashoka; this account seems to be influenced by the Nigrodha story.

The A-yu-wang-chuan states that a 7-year-old Buddhist converted Ashoka. Another story claims that the young boy ate 500 Brahmanas who were harassing Ashoka for being interested in Buddhism; these Brahmanas later miraculously turned into Buddhist bhikkus at the Kukkutarama monastery, where Ashoka paid a visit.

Several Buddhist establishments existed in various parts of India by the time of Ashoka’s ascension. It is not clear which branch of the Buddhist sangha influenced him, but the one at his capital Pataliputra is a good candidate. Another good candidate is the one at Mahabodhi: the Major Rock Edict 8 records his visit to the Bodhi Tree – the place of Buddha’s enlightenment at Mahabodhi – after his 10th regnal year, and the minor rock edict issued during his 13th regnal year suggests that he had become a Buddhist around the same time.

Support for Buddhism

The Buddhist tradition holds many legends about Ashoka. Some of these include stories about his conversion to Buddhism, his support of the monastic Buddhist communities, his decision to establish many Buddhist pilgrimage sites, his worship of the bodhi tree under which the Buddha attained enlightenment, his central role organizing the Third Buddhist Council, followed by the support of Buddhist missions all over the empire and even beyond as far as Greece, Egypt and Syria. The Buddhist Theravada tradition claims that a group of Buddhist missionaries sent by Emperor Ashoka introduced the Sthaviravada school (a Buddhist school no longer existent) in Sri Lanka, about 240 BCE.

|

| Ashoka’s pillar erected in the district of Vaishali, located in the Bihar state, India. |

It is not possible to know which of these claims are actual historical facts. What we do know is that Ashoka turned Buddhism into a state religion and encouraged Buddhist missionary activity. He also provided a favourable climate for the acceptance of Buddhist ideas, and generated among Buddhist monks certain expectations of support and influence on the machinery of political decision making. Prior to Ashoka Buddhism was a relatively minor tradition in India and some scholars have proposed that the impact of the Buddha in his own day was relatively limited. Archaeological evidence for Buddhism between the death of the Buddha and the time of Ashoka is scarce; after the time of Ashoka it is abundant.

A PARTICULAR STORY TELLS THAT ASHOKA BUILT 84,000 STUPAS.

Was Ashoka a true follower of the Buddhist doctrine or was he simply using Buddhism as a way of reducing social conflict by favouring a tolerant system of thought and thus make it easier to rule over a nation composed of several states that were annexed through war? Was his conversion to Buddhism truly honest or did he see Buddhism as a useful psychological tool for social cohesion? The intentions of Ashoka remain unknown and there are all types of arguments supporting both views.

Family of Ashoka

Queens

Various sources mention five consorts of Ashoka: Devi (or Vedisa-Mahadevi-Shakyakumari), Karuvaki, Asandhimitra (Pali: Asandhimitta), Padmavati, and Tishyarakshita (Pali: Tissarakkha).

Kaurvaki is the only queen of Ashoka known from his own inscriptions: she is mentioned in an edict inscribed on a pillar at Allahabad. The inscription names her as the mother of prince Tivara, and orders the royal officers (mahamattas) to record her religious and charitable donations. According to one theory, Tishyarakshita was the regnal name of Kaurvaki.

|

| A king – most probably Ashoka – with his two queens and three attendants, in a relief at Sanchi. The king’s identification with Ashoka is suggested by a similar relief at Kanaganahalli, which bears his name. |

According to the Mahavamsa, Ashoka’s chief queen was Asandhimitta, who died four years before him. It states that she was born as Ashoka’s queen because in a previous life, she directed a pratyekabuddha to a honey merchant (who was later reborn as Ashoka). Some later texts also state that she additionally gave the pratyekabuddha a piece of cloth made by her. These texts include the Dasavatthuppakarana, the so-called Cambodian or Extended Mahavamsa (possibly from 9th–10th centuries), and the Trai Bhumi Katha (15th century). These texts narrate another story: one day, Ashoka mocked Asandhamitta was enjoying a tasty piece of sugarcane without having earned it through her karma.

Asandhamitta replied that all her enjoyments resulted from merit resulting from her own karma. Ashoka then challenged her to prove this by procuring 60,000 robes as an offering for monks. At night, the guardian gods informed her about her past gift to the pratyekabuddha, and next day, she was able to miraculously procure the 60,000 robes. An impressed Ashoka makes her his favourite queen, and even offers to make her a sovereign ruler. Asandhamitta refuses the offer, but still invokes the jealousy of Ashoka’s 16,000 other wives. Ashoka proves her superiority by having 16,000 identical cakes baked with his royal seal hidden in only one of them.

Each wife is asked to choose a cake, and only Asandhamitta gets the one with the royal seal. The Trai Bhumi Katha claims that it was Asandhamitta who encouraged her husband to become a Buddhist, and to construct 84,000 stupas and 84,000 viharas.

According to Mahavamsa, after Asandhamitta’s death, Tissarakkha became the chief queen. The Ashokavadana does not mention Asandhamitta at all, but does mention Tissarakkha as Tishyarakshita. The Divyavadana mentions another queen called Padmavati, who was the mother of the crown-prince Kunala.

As mentioned above, according to the Sri Lankan tradition, Ashoka fell in love with Devi (or Vidisha-Mahadevi), as a prince in central India. After Ashoka’s ascention to the throne, Devi chose to remain at Vidisha than move to the royal capital Pataliputra. According to the Mahavmsa, Ashoka’s chief queen was Asandhamitta, not Devi: the text does not talk of any connection between the two women, so it is unlikely that Asandhamitta was another name for Devi. The Sri Lankan tradition uses the word samvasa to describe the relationship between Ashoka and Devi, which modern scholars variously interpret as sexual relations outside marriage, or co-residence as a married couple. Those who argue that Ashoka did not marry Devi argue that their theory is corroborated by the fact that Devi did not become Ashoka’s chief queen in Pataliputra after his ascension. The Dipavamsa refers to two children of Ashoka and Devi – Mahinda and Sanghamitta.

Sons

Tivara, the son of Ashoka and Karuvaki, is the only of Ashoka’s sons to be mentioned by name in the inscriptions.

According to North Indian tradition, Ashoka had a son named Kunala. Kunala had a son named Samprati.

The Sri Lankan tradition mentions a son called Mahinda, who was sent to Sri Lanka as a Buddhist missionary; this son is not mentioned at all in the North Indian tradition. The Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang states that Mahinda was Ashoka’s younger brother (Vitashoka or Vigatashoka) rather than his illgetimate son.

The Divyavadana mentions the crown-prince Kunala alias Dharmavivardhana, who was a son of queen Padmavati. According to Faxian, Dharmavivardhana was appointed as the governor of Gandhara.

The Rajatarangini mentions Jalauka as a son of Ashoka.

Daughters

According to Sri Lankan tradition, Ashoka had a daughter named Sanghamitta, who became a Buddhist nun. A section of historians, such as Romila Thapar, doubt the historicity of Sanghamitta, based on the folloiwng points:

- The name “Sanghamitta”, which literally means the friend of the Buddhist Order (sangha), is unusual, and the story of her going to Ceylon so that the Ceylonese queen could be ordained appears to be an exaggeration.

- The Mahavamsa states that she married Ashoka’s nephew Agnibrahma, and the couple had a son named Sumana. The contemporary laws regarding exogamy would have forbidden such a marriage between first cousins.

- According to the Mahavamsa, she was 18 years old when she was ordained as a nun. The narrative suggests that she was married two years earlier, and that her husband as well as her child were ordained. It is unlikely that she would have been allowed to become a nun with such a young child.

Another source mentions that Ashoka had a daughter named Charumati, who married a kshatriya named Devapala.

Brothers

According to the Ashokavadana, Ashoka had an elder half-brother named Susima. According to the Sri Lankan tradition, Ashoka killed his 99 half-brothers.

Various sources mention that one of Ashoka’s brothers survived his ascension, and narrate stories about his role in the Buddhist community.

- According to Sri Lankan tradition, this brother was Tissa, who initially lived a luxurious life, without worrying about the world. To teach him a lesson, Ashoka put him on the throne for a few days, then accused him of being an usurper, and sentenced him to die after seven days. During these seven days, Tissa realised that the Buddhist monks gave up pleasure because they were aware of the eventual death. He then left the palace, and became an arhat.

- The Theragatha commentary calls this brother Vitashoka. According to this legend, one day, Vitashoka saw a grey hair on his head, and realised that he had become old. He then retired to a monastery, and became an arhat.

- Faxian calls the younger brother Mahendra, and states that Ashoka shamed him for his immoral behaviour. The brother than retired to a dark cave, where he meditated, and became an arhat. Ashoka invited him to return to the family, but he preferred to live alone on a hill. So, Ashoka had a hill built for him within Pataliputra.

- The Ashoka-vadana states that Ashoka’s brother was mistaken for a Nirgrantha, and killed during a massacre of the Nirgranthas ordered by Ashoka.

Last years of Ashoka

Tissarakkha as the queen

Ashoka’s last dated inscription – the Pillar Edict 4 is from his 26th regnal year. The only source of information about Ashoka’s later years are the Buddhist legends. The Sri Lankan tradition states that Ashoka’s queen Asandhamitta died during his 29th regnal year, and in his 32nd regnal year, his wife Tissarakkha was given the title of queen.

Both Mahavamsa and Ashokavadana state that Ashoka extended favours and attention to the Bodhi Tree, and a jealous Tissarakkha mistook “Bodhi” to be a mistress of Ashoka. She then used black magic to make the tree wither. According to the Ashokavadana, she hired a sorceress to do the job, and when Ashoka explained that “Bodhi” was the name of a tree, she had the sorceress heal the tree. According to the Mahavamsa, she completely destroyed the tree, during Ashoka’s 34th regnal year.

The Ashokavadana states that Tissarakkha (called “Tishyarakshita” here) made sexual advances towards Ashoka’s son Kunala, but Kunala rejected her. Subsequently, Ashoka granted Tissarakkha kingship for seven days, and during this period, she tortured and blinded Kunala. Ashoka then threatened to “tear out her eyes, rip open her body with sharp rakes, impale her alive on a spit, cut off her nose with a saw, cut out her tongue with a razor.” Kunala regained his eyesight miraculously, and pleaded for mercy on the queen, but Ashoka had her executed anyway. Kshemendra’s Avadana-kalpa-lata also narrates this legend, but seeks to improve Ashoka’s image by stating that he forgave the queen after Kunala regained his eyesight.

Death

According to the Sri Lankan tradition, Ashoka died during his 37th regnal year, which suggests that he died around 232 BCE.

According to the Ashokavadana, the emperor fell severely ill during his last days. He started using state funds to make donations to the Buddhist sangha, prompting his ministers to deny him access to the state treasury. Ashoka then started donating his personal possessions, but was similarly restricted from doing so. On his deathbed, his only possession was the half of a myrobalan fruit, which he offered to the sangha as his final donation. Such legends encourage generous donations to the sangha and highlight the role of the kingship in supporting the Buddhist faith.

Legend states that during his cremation, his body burned for seven days and nights.

Ashoka’s Legacy

The myths and stories about Ashoka propagating Buddhism, distributing wealth, building monasteries, sponsoring festivals, and looking after peace and prosperity served as an inspiring model of a righteous and tolerant ruler that influenced monarchs from Sri Lanka to Japan. A particular story tells that Ashoka built 84,000 stupas (commemorative Buddhists buildings used as a place of meditation), served as an example to many Chinese and Japanese rulers who imitated Ashoka’s initiative.

He did with Buddhism in India what Emperor Constantine did with Christianity in Europe and what the Han dynasty did with Confucianism in China: he turned a tradition into an official state ideology and thanks to his support Buddhism ceased to be a local Indian cult and began its long transformation into a world religion. Eventually, Buddhism died out in India sometime after Ashoka’s death, but it remained popular outside its native land, especially in eastern and south-eastern Asia. The world owes to Ashoka the growth of one of the world’s largest spiritual traditions.